Dedicated to all the children who entrusted us with their stories, and to all those who continue to bravely make the incredible journey here in search of safety and a better life.

IN THIS REPORT:

-Introduction

-A Landscape Barren of Rights

-The Flores Settlement Agreement

-The Rights of Unaccompanied Children

-Standing Up For Children: The Role of a Shelter Advocate

-Thousands of Voices: Scope and Overall Findings

-Can You Hear Me? The Invisibilization of Indigenous Immigrants

-Unsanitary Conditions: Lack of Basic Necessities at Border Detention Facilities

-Where’s the Baby Food? The Lack of Age-Appropriate Food and Its Consequences

-When the Most Vulnerable are the Least Protected: Illness and Medical Care in Custody

-Juan’s Story: A Minor’s 58 Perilous Days in Adult Detention

-Detention as Punishment: 72+ Hours of Physical and Verbal Abuse

-Brigitt’s Story: The Right to Be Oneself

-Unprecedented: Recent Policies Affecting Unaccompanied Minors

-“It Was Despairing”: Reflections on Detention at the Border

-Where Do We Go From Here? Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations

-Endnotes

Do My Rights Matter: The Mistreatment of Unaccompanied Children in CBP Custody

Released October 2020

Download the full report (PDF)

For years, thousands of children have made the difficult decision to flee from their countries with the hope of securing safety and security in the United States. Their reasons for fleeing vary but there are common themes. Many of these children are seeking protection from human trafficking, targeted gang violence in the form of assaults, kidnappings, or extortions, as well as domestic violence and child abuse.

In 2019 alone, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) detained over 76,000 children. As part of our investigation into the treatment of unaccompanied children and conditions at the facilities at the border, we interviewed and provided legal services to 9,417 of them.

This report is based on these unaccompanied children’s testimonies of being detained at US detention facilities along the southern border. Children were detained in horrific conditions way beyond the 72 hours allowed under US law. Children described being held in frigid rooms, sleeping on concrete floors, being fed frozen food, with little or no access to medical care. Too often, they were subjected to emotional, verbal, and physical abuse by CBP officers.

A Landscape Barren of Rights

By Jennifer Anzardo Valdes

For years, thousands of unaccompanied children1 have made the difficult decision to flee from their countries with the hope of securing safety and security in the United States. Their reasons for fleeing vary but there are common themes. Many of these children are seeking protection from human trafficking, targeted gang violence in the form of assaults, kidnappings, or extortions, as well as domestic violence and child abuse.

Unfortunately, although many of these children come seeking refuge, they often suffer an inhumane and cruel experience in their first encounter with the US government that leads to further trauma. In fiscal year 2019, conditions in the holding facilities at the border were dire. Children, including babies, were held in deplorable and unsanitary conditions. After almost a decade without child deaths in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody, at least five deaths of innocent children have been reported since December 2018.2 CBP detained a record setting 76,020 unaccompanied children in 2019.3 Under US law, when an unaccompanied child crosses the border and is apprehended by CBP, CBP processes the child and is required to transfer them to the custody of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours.4

Since 1997, the Flores Settlement Agreement has set minimum standards for children detained by the federal government, including that children in CBP custody should be placed in “safe and sanitary” holding facilities.5 However, the stories we hear from our clients and from reports across the United States paint a very different picture.

In the series of articles that follow, we highlight the stories collected from more than 9,000 children we interviewed between January 2019 and October 2019. Children were detained in horrific conditions way beyond the 72 hours allowed under US law. Children described being held in frigid rooms, sleeping on concrete floors, being fed frozen food, with little or no access to medical care. Too often, they were subjected to emotional, verbal, and physical abuse by CBP officers.

In summer 2019, advocates, whistleblowers, the media and members of Congress called attention to the unsafe and unsanitary conditions at the border holding facilities. The Office of Inspector General released a report which found that more than 2,000 unaccompanied children were being held in overcrowded facilities on any given day and that 31% of those children had been in custody longer than 72 hours.6 Additionally, more than 50 of these children were under the age of seven and in custody for more than two weeks.7 The public outcry seemed to only fuel the Trump administration’s attempt to continue to dehumanize and strip protections from these vulnerable children. Instead of trying to fix the crisis, the administration took steps to significantly worsen it. In June 2019, the administration argued before a Ninth Circuit court panel that it should not be required to provide children in CBP custody with basic toiletries, such as soap and toothbrushes, or provide adequate sleeping arrangements.8 Shortly after the Ninth Circuit panel ruled against the administration, the administration released regulations that attempted to terminate the Flores agreement and significantly worsen conditions. Thankfully, these regulations were also blocked by a federal court.9 The government often argues that these conditions exist because of lack of resources and the influx of large numbers of children. However, CBP’s resources are abundant, and unaccompanied children seeking protection at our borders is nothing new. CBP is the largest federal law enforcement agency, and it has seen its workforce double since 2003.10 Additionally, it has seen a significant increase in funding over the years, including in 2019.11 Despite these resources and years of experience in detaining thousands of children, the agency has failed to make changes, and reports of horrific conditions in their facilities continue. Americans for Immigrant Justice (AI Justice) has spent more than two decades documenting and litigating the mistreatment of asylum seekers, including children, at the hands of CBP. How many more children have to die for CBP to effectuate change? The impact of these abusive practices on the children will be long-lasting. These vulnerable children deserve to be welcomed with compassion and respect as they seek refuge and a better life in the United States.

The Flores Settlement Agreement

What is the Flores Settlement Agreement?

In 1985, civil liberties and immigration rights groups filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of immigrant children that challenged the detention and treatment of children by what was then known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). In 1997, after more than a decade of contentious litigation, the parties reached a settlement known as the Flores Settlement Agreement. The lawsuit arose from lead plaintiff Jenny Lisette Flores, a 15-year-old Salvadoran girl. She alleged that during her two-month detention she was subjected to strip searches and was forced to share a living space and bathrooms with adult men. Additionally, INS refused to release her to family members, and were requiring that her sponsor be a legal guardian. The Flores Settlement Agreement ushered in new protections for the care, custody, and release of detained immigrant children.

Why is Flores Important?

Flores is essential to preventing the abuse or neglect of minors in federal custody. The federal government is bound by Flores to adhere to basic standards regarding the care and release of immigrant children in federal custody, whether alone or with families. By the agreement, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its agencies are required to treat all children with “dignity, respect, and special concern for their particular vulnerability as minors.”

What are some of the agreements in the Flores settlement?

- Minors in DHS custody shall be expeditiously processed and provided with a notice of rights.

- Facilities that house children must be sanitary, temperature-controlled and ventilated. DHS facilities must supply food, clean drinking water and drinking cups, medical and dental care, immunizations, medications, an assessment identifying immediate family members in the United States and contact with family members.

- DHS facilities must supply hygiene items, bedding, and clothes.

- Each child in custody is entitled to an individualized needs assessment, an educational assessment and plan, a statement of religious preferences, education services and communication skills, English-language training, recreation and leisure time, and access to social work staff and counseling sessions at DHS facilities.

- Children shall not be held with unrelated adults, and facility officials must provide adequate supervision.

- Children shall be placed in the “least restrictive setting” appropriate to their age and any special needs.

- Children shall be released from immigration detention without unnecessary delay and placed with, in order of preference, parents, other adult relatives or licensed programs willing to accept custody.

The Rights of Unaccompanied Children

In an effort to combat human trafficking and other forms of exploitation, the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008 passed with bipartisan support and was signed by former President George W. Bush. It created a separate procedure for processing unaccompanied children.

Protections Provided by the TVPRA

- CBP has 48 hours to designate a child as an unaccompanied child (UC) and is then required to transfer the child to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours.

- When an unaccompanied child turns 18, the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should consider the “least restrictive setting” when making custody determinations.

- Unaccompanied children, except those from contiguous countries who agree to voluntarily return, shall be provided with formal removal proceedings before an Immigration Judge.

- Children from contiguous countries (i.e., Mexico and Canada) shall be screened by DHS for trafficking and fear of return. If the child expresses fear or is at risk of being trafficked, the child is then processed as an unaccompanied child. If the child does not express fear and is not at risk of being trafficked, the child is returned to their home country.

- Unaccompanied children have access to counsel, to the greatest extent possible, to represent them in their legal proceedings, at their own expense.

- Asylum:

- Unaccompanied children are not bound by the one-year asylum filing deadline.

- Unaccompanied children are given the opportunity to have their cases heard before USCIS Asylum Office through a more child-appropriate interview process conducted by Asylum Officers who have received training on child interviewing and the adjudication of children’s cases. If an asylum office does not approve the application, it is referred to an Immigration Judge, and the child is able to present their claim again

- The definition of Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) was expanded to include children who are dependent and/or placed in the custody of an individual or entity and are unable to reunify with one or both parents due to abuse, neglect, abandonment or a similar basis under state law.

SOURCES: “Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act Safeguards Children.” National Immigration Forum, 23 May 2018, www.immigrationforum.org/article/traffickingvictims-protection-reauthorization-act-safeguards-children/. U.S. Congress; Public Law 110- 457. William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. www. congress.gov/110/plaws/publ457/PLAW-110publ457.pdf; U.S. Congress, Office of Inspector General. CBP’s Handling of Unaccompanied Alien Children, Sept. 2010, www.trac.syr.edu/ immigration/library/P5017.pdf; Wasem, Ruth Ellen. Asylum Policies for Unaccompanied Children Compared with Expedited Removal Policies for Unauthorized Adults: In Brief. Congressional Research Service, 2014, www.fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43664.pdf.

Standing Up For Children: The Role of a Shelter Advocate

By Maria Valentina Eman

A shelter advocate provides Know Your Rights (KYR) presentations and legal screenings to detained minors at Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facilities in Spanish, English, or any other language with the assistance of an interpreter. Advocates inform children of their rights and responsibilities at the shelter and after release. The presentation covers finding an attorney after release from ORR custody, going to immigration court, and what to do if an immigration or police officer approaches you or arrives at your home.

A legal screening with a shelter advocate is a child’s first step to building a legal case in the United States, as well as the first confidential meeting with a legal professional while in ORR custody. Shelter advocates and attorneys work closely to ensure detained children and teens receive legal services.

Case management is a big part of a shelter advocate’s job. Advocates monitor reunification cases, work with children who have no sponsors, repeatedly meet with minors who have been at the shelter for several weeks, as well as provide further legal screenings. All cases are monitored, and updates are reported in the case management database so the entire team of shelter advocates and attorneys at AI Justice may monitor the progress of each child’s case.

Shelter advocates promote and defend the legal rights of this extremely vulnerable population, providing assistance that has become more critical in an increasingly anti-immigrant environment.

«Being a shelter advocate has fueled my drive to help amplify those voices that so often go unheard. These children are escaping violence and poverty, leaving everything they’ve ever known to try and better their lives in the land of opportunity. It is our duty and privilege as their confidantes to make sure they are heard.»

— Maria Valentina Eman

“It was 2014 when I first learned that there was a surge of unaccompanied children, mostly from Central America, crossing the border — the same border my parents crossed decades before. I knew then that I wanted to help but didn’t know how. Years later, I discovered the shelter advocate role at AI Justice. As a daughter of Guatemalan immigrants growing up in a largely Central American neighborhood, my work as a shelter advocate is, at times, a deeply personal mission. Unaccompanied children come from all over, and it is an honor to be someone in their journey they can finally confide in and tell their story to truthfully, or in their native language, or with the tools necessary; someone who gives them that chance to complain or cry; someone who reminds them that, although their journey does not end when they leave the shelter, and the end is uncertain, there are people like us who welcome them.”

— Genesis Barrios

“I had an eye-opening and rewarding moment, when at the end of an intake, a minor said to me: ‘It doesn’t matter if you can’t find me a lawyer, I am really happy someone was willing to listen to my story. I needed to get this off my chest.’ ”

— Lia Mora

“Having been a shelter advocate for over three years has afforded me the opportunity to see through the unique lens of hundreds of children and how they navigate and process — not only a highly complex immigration system but also unimaginable experiences of trauma, violence, poverty and neglect. Often, I find these kids to be inspirational and full of hope, strong and wise beyond their years. After listening to their stories, it is almost impossible not to come away with a steadier determination to continue doing this work.”

— Rosario Paz

“To me, a shelter advocate is someone who listens to and stands up for children who might otherwise not be heard, for children who don’t know that they can be heard. A shelter advocate doesn’t just advocate for these children, but teaches them that they have rights, that they should share their stories and that they should stand up for themselves as well.”

— Sofia Aumann

“I am in awe every time I stand before a group of minors. These children have crossed countries, left everything they have ever known, and journeyed towards the unknown. As an advocate, it is a privilege to be a part of their journey.”

— Janette Vargas

Thousands of Voices: Scope and Overall Findings

By Lily Hartmann and Rosario Paz

As part of our investigation into the treatment of unaccompanied children and conditions at the facilities at the border, we looked at information from 9,417 children screened by our staff in South Florida between January 1, 2019, and October 15, 2019.

The children ranged in age from 24 days to 18 years old. They were apprehended and detained at different points along the southern US-Mexico border, including Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California.

We followed up with 18 (14 questionnaires and four nonstructured interviews) children through in-depth phone or in-person interviews in order to obtain more details on the mistreatment each child faced while detained.

This report is based on the testimonials of thousands of unaccompanied children who were detained at several US detention facilities along the southern border.

Overall Findings

Although each child told us about their personal journey to the United States and what they faced in US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody, many voiced similar complaints about their treatment in the CBP border facilities.

The most common complaint was that the border facilities are kept at frigid temperatures that leave the children cold and uncomfortable. CBP standards require Border Patrol officers to “maintain hold room temperature within a reasonable and comfortable range for both detainees and officers/agents.”12 However, 69% of the children we interviewed reported that the facilities they were detained in were noticeably cold, so cold that immigrants refer to them as hieleras, or iceboxes. Many children arrive in wet clothes or are ill from their difficult journeys to the United States. These cold temperatures lead to the spread of illness within the facilities. Children reported being provided only flimsy mylar aluminum blankets to keep warm.

More than half of the children reported that they were detained at the border for more than 72 hours, despite the Flores Settlement Agreement requiring that minors remain in CBP custody no more than 72 hours.13 The average length of stay in CBP custody for the children we spoke to was 10 days.14 This far exceeds the 72-hour limit promulgated by the Flores agreement and later codified in the 2008 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA).15

During their prolonged detention at the border, unaccompanied children had limited access to phones to call their loved ones and were unable to speak to a lawyer or anyone who could advocate for them. As a result, few children understood why it took so long for them to be transferred to an Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facility.

Another major issue was a lack of food and water. Children told us they were underfed or that the food they were given was inedible. CBP’s own standards require that children “will be offered a snack upon arrival and a meal at least every six hours thereafter, at regularly scheduled mealtimes. At least two of those meals will be hot.”16 Additionally, the food provided “must be in edible condition (not frozen, expired, or spoiled),” and children “must have regular access to snacks, milk, and juice.”17 Under CBP’s standards, “[f]unctioning drinking fountains or clean drinking water along with clean drinking cups must always be available to detainees.”18

Most children were given food two or three times each day, but they often did not eat because the food was frozen, rotten, or generally inedible. Meals included a burrito, an apple, and a bottle of water at some border facilities; at others, it was a sandwich with frozen ham, milk, and potato chips. The meals were repetitive, the burritos were often cold, and the meat in the sandwiches smelled rotten. One child told us, “The food upset my stomach, so I didn’t really eat it.” Doctors who have screened migrants detained in CBP facilities in the Tucson, Arizona, sector found that about 80% of migrants said they had abdominal or stomach pain after eating the burritos they were given.19

Most of the children we interviewed said they went hungry at the border facility. Some children could not get water — “they would give us a little water bottle for the day, and sometimes the next day, they wouldn’t give [a water bottle] to us until the afternoon.” Another child explained, “[The officers] told [us] to drink from where we washed our hands [in] the bathroom.”

Other common issues reported by minors included overcrowding in the cells, limited access to showers and hygiene products like toothbrushes, and being detained with adults.20 Sintia, a 17-year-old girl from Honduras said: “At first, we were all mixed in one cell as we got processed. Then, the [officers] moved us to other cells. They were fenced-in cells. It was in the first mixed cells that we were like sardines in a can; it was very packed.” In the cells where the children were held as they waited to be sent to a shelter, the lights stayed on all day and night, making it difficult to sleep. Almost all the children we interviewed said the facilities were very noisy because babies and children would be crying, and officers would constantly be yelling out people’s names and other commands.

Most of the children arrived in clothes they had worn for weeks throughout their arduous journey, and they generally had to stay in those clothes throughout their detention. If they arrived with a coat or a sweater, or extra clothes, officers took them away.

Dulce, a teenager from El Salvador, traveled to the United States with her two-year-old child. When immigration officers apprehended Dulce, her child and her sister near El Paso, Texas, the officers took them in a car to a detention center, where they were interviewed and held in a cold room for a few hours. Without explanation, they were then taken to another facility, where there were only children and teens. They stayed there for 20 days. Dulce wore the same clothes for the entire time; the officers did not provide her with any clothes or allow her to wash what she was wearing. She was only able to shower twice during her three weeks in CBP custody.

Dulce brushed her teeth with a toothbrush and toothpaste only three times while at the border. When she asked an official if she could brush her teeth, they said that they were not allowed to provide toothbrushes. The cell to which Dulce, her sister, and daughter were assigned was severely overcrowded. There were only two toilets for 55 girls, and the cell was so full that there was no space to sit down. “I was affected by this because I was in there with my daughter and we were enclosed there. My daughter would bang on the doors because she wanted to get out and we couldn’t leave.”

Can You Hear Me? The Invisibilization of Indigenous Immigrants

By Sofia Aumann, Genesis Barrios, Maria Valentina Eman, Lia Mora, Rosario Paz, and Janette Vargas

Disclaimer: This section is intended to be a brief overview of the migration of Indigenous peoples to the United States, specifically Indigenous people of the Americas. We would like to acknowledge that we are not Indigenous. We urge readers to listen to and amplify Indigenous voices first and foremost without assuming their needs and desires.

In fiscal year 2019, 73,235 unaccompanied children from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador were apprehended at the southern border of the United States.21 Of those minors, 30,329 were Guatemalans, making up almost 42% of the total.22 Many of these children, especially those from Guatemala, are Indigenous and speak an Indigenous language.

There are numerous Indigenous cultures and communities throughout Mexico, Central and South America. In Latin America, these cultures consist of their own languages and their own social norms, distinct from Hispanic/Latinx23 culture. When Indigenous peoples from Latin America migrate to the United States, they face many obstacles, misunderstandings and miscommunications, which stem from the lack of appropriate interpreter services and language accommodations from government agencies. The language exclusion and cultural erasure as a distinct people that Indigenous people face leads to a plethora of consequences, especially within the immigration system.24

Among the children interviewed for this report, we found children spoke 29 distinct indigenous languages, 25 of which are from the Americas, 3 from Africa, and one unidentified. Of the 9,417 children we interviewed, 1,850 spoke Indigenous languages, 13% of whom required an interpreter. We believe the actual number of children who are Indigenous and/or require an interpreter is much higher. In some cases, they do not disclose their Indigenous background or their need for an interpreter because of discrimination in their home countries.

About 20% of the children screened during our report’s timeframe identified as speaking at least one Indigenous language. Indigenous children reported a higher percentage of CBP mistreatment than non-Indigenous children. About 92% of Indigenous children we interviewed reported CBP mistreatment, compared with 85% of non-Indigenous minors.

Historical Context

The transnational migration of Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous children from Latin America to the United States over the last few decades, has defied the myth of Indigenous peoples as a “static,” never changing, disappearing people.25 Their growing presence within the United States redefines what it means for Indigenous peoples to flee their ancestral lands, cross national borders26 and establish themselves in a country such as the United States, whose own native communities have been violently decimated, displaced, and are largely absent from popular discourse.27

The First Waves of Migration: 1980s to 1996

Most of the Indigenous immigrant children we work with are of different Maya ethnolinguistic groups from Guatemala. The first waves of their mass migration north started in the early 1980s. This historic forced migration is captured in the 1983 Oscar-nominated film El Norte (“The North”), directed by Gregorio Nava.

El Norte tells the story of Enrique and Rosa Xuncax, two Maya Q’anjob’al28 siblings who decide to migrate to “el Norte” after their father is murdered for trying to organize a union with other coffee pickers. Their mother is later abducted by military forces and is never seen again. Fearing for their lives, Rosa and Enrique leave Guatemala and journey through Mexico, just like the hundreds of thousands29 of people who fled from the civil war that plagued Guatemala from 1960 to 1996.

The civil war surged as leftwing guerilla groups resisted US-backed Guatemalan military regimes.30 According to the UN Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), agents of the Guatemalan state, which included the Army, Civil Patrols, death squads, security forces, and military commissioners, were the major perpetrators of the violence and human rights violations during the civil war.31

State military forces targeted the Indigenous Maya, whom they believed to be allies of the guerrilla movement.32 The Army and other state forces carried out 626 registered massacres, which involved rape, stealing children for adoption, and other atrocious acts, such as cutting open pregnant women’s wombs. State military forces also carried out “scorched earth” operations, burning fields, harvests, crops and resources. The Army also destroyed sacred Mayan places and cultural symbols, as well as entire villages, wiping out many Maya rural communities.

The horrific violence and devastation of entire villages led to massive displacement of the Indigenous Maya. Estimates on the number of people forcibly displaced range from half a million to 1.5 million people. During the 36-year civil war, more than 200,000 people were killed or disappeared. Of the victims who were identified, 83% were Maya. In 1999, the CEH declared that the agents of the Guatemalan state committed genocide against the Maya, particularly in the regions of the Maya Q’anjob’al, Maya Chuj, Maya lxil, Maya K’iche’ and Maya Achi, in the western and northwestern regions of Guatemala.33

Despite seeking refuge in the United States from the genocide, many Mayas never sought asylum nor were they granted refugee status.34 The United States was generally unwilling to grant them asylum, having backed the dictatorships responsible for the violence the Maya were fleeing.35

Although the civil war officially ended in 1996 with the signing of peace accords, post-war Guatemala has been characterized by economic and political instability, as well as ongoing marginalization and oppression of the Indigenous Maya. This has driven more mass migration to southern Mexico, the United States and Canada. In the United States, the Maya of Guatemala have established large communities, mainly in California, Texas, and our own state of Florida.36

Current Waves of Migration: 1996 to Now

As to why Indigenous peoples are continuing to migrate, Lopez, Gonzales, and Gentry, directors of the International Mayan League, Indigenous Alliance without Borders, and Indigenous Languages Office, respectively, offer a more complex explanation that goes beyond economic reasons. Indigenous forced migration, they say, results from a history of marginalization, “conflicts over lands and resources, racist and discriminatory laws and policies, imposed development, debilitating poverty, and now, climate change.”37

Most migrants now heading to the United States are from Guatemala, with most coming from the Western Highlands, which are predominantly rural and Indigenous areas.38 Among the factors pushing the Maya to migrate:

- Imposed Development. Multinational extractive industries,39 including mining, palm oil production,40 and hydroelectric projects, have developed without the input of Indigenous communities in Guatemala,41 leading to their evictions and displacement. These projects have also led to dire environmental consequences, such as the contamination of water and land, on Indigenous lands. This harms the health, the agricultural livelihood,42 and the food security of the Maya. Given recent murders and migration of Maya environmental activists, the Maya have not been able to defend their communities without risking their lives.43 These are the same lands that were devastated during the civil war.

- Conflict over lands and resource. The Maya were promised special land rights in the peace accords, but this has not come about.44

- Debilitating Poverty. Four of every five Indigenous persons in Guatemala, or 80%, were living in total poverty, according to Guatemala’s 2014 National Survey of Living Conditions (ENCOVI).45 About 40% were living in extreme poverty, compared with 13% of the non-Indigenous population.46

- Climate Change. Guatemala is one of the world’s 10 most vulnerable nations to climate change.47 The rise of heavy rainstorms or drought, brought about by climate change, has threatened agricultural production and thus food security.48 The drop in the production and price of coffee has also threatened farming as a livelihood.49

Understanding this history explains why the children of these Maya communities choose to migrate; migration serves as a survival strategy. Family reunification is a more common reason for the migration of Indigenous children than it is for non-Indigenous children.50

Why is This Information Important?

It is important to make the distinction that Indigenous cultures from Mexico, Central America, and South America are not the same as the Hispanic and/or Latinx cultures that Americans commonly associate with immigrants from Latin America.

Indigenous peoples from Guatemala and Mexico often see themselves as Indigenous first and Guatemalan or Mexican second. Their social norms are informed not by the Hispanic culture of Guatemala, but by their Indigenous culture. Many Indigenous people speak little or no Spanish, instead primarily speaking their own Indigenous language. The following case of a young Indigenous girl from Guatemala who arrived at the border with her mother illustrates the problems. Juliana was separated from her mother and each was interviewed by patrol officers in different rooms. They were asked questions in Spanish about where they lived, where they went to school or church and the colors of the buildings.

Because Juliana’s mother was not fluent in Spanish like her daughter, she answered one of the questions with a different color than her daughter did. As a result, officers said that they were not mother and daughter and accused them of lying. Juliana was transferred to an ORR facility without her mother and labeled an unaccompanied child. Such incidents illustrate the language barrier Indigenous people face upon migrating to the United States. That barrier is just the beginning of the erasure of their identities as they navigate the hurdles of the US immigration system.

Approximately

6,700

languages are spoken worldwide

4,000+

of the world’s languages are spoken by Indigenous peoples

At least

560

Indigenous languages are spoken in Latin America

29

The number of distinct Indigenous languages that unaccompanied children AI Justice screened from Jan. 1 to Oct. 15, 2019 reported speaking. One of the 29 languages went unidentified.

The Ethnolinguistic Diversity of Indigenous Migrant Children We Served in 2019

According to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, approximately 6,700 languages are spoken around the world. Out of the world’s languages, more than 4,000 are spoken by Indigenous peoples.51 Within Latin America, at least 560 Indigenous languages are spoken.52 The Indigenous immigrant children we served in 2019 demonstrate the rich diversity of Indigenous languages.

The Consequences of Invisibilization

A collaborative report written by members of the Indigenous Language Office, Indigenous Alliance Without Borders, and the International Mayan League, among others, titled “Promising Practices for Legal Assistance to Indigenous Children in Detention” (2020), recommends a different practice for interacting with and assisting Indigenous children in detention. The report emphasizes the immense consequences to the Indigenous child’s psychological, emotional and cognitive state when their culture is ignored, and their language is excluded.

It is important to understand that “Indigenous children understand the Indigenous culture they came from, and they know that their culture does not exist in detention.”53 Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers generally assume that Indigenous migrants are monolingual, Spanish-speaking, Hispanic immigrants. They initially address these Indigenous people in Spanish, if not English, completely ignoring that the people they are interacting with might not understand what they are saying.

This is often incredibly stressful and shameful, and therefore traumatizing, for children fleeing discrimination and persecution for being Indigenous. During our experience as legal service providers, we have noticed that many Indigenous children are ashamed to speak up about their Indigenous culture and language preference. Even when they do request interpreter services, not only is it extremely difficult to find appropriate interpreters, but ICE and CBP officers frequently do not put in the effort to find appropriate interpretation services.

The lack of empathy from governmental agencies has created a systemic problem that makes every step of the immigration process in the United States incredibly difficult.

Take the story of Pedro, an 8-year-old Indigenous child from Guatemala and an AI Justice client. Pedro crossed the southern border of the United States with his father in August 2017, where five immigration officers apprehended them and separated Pedro from his father. Pedro, who speaks Akateko, didn’t understand what was happening. When telling us about his experience, through an interpreter, Pedro recalled the traumatic experience of screaming and crying as immigration officers threw his father to the ground, stomping on him, and took him away. Pedro received no explanation in his native language of Akateko. All he understood was that he was now without his father. This lack of cultural awareness and the blatant disregard for appropriate language access added tremendous stress to an already traumatizing experience for Pedro.

Unaccompanied children who migrate to the United States by crossing the Southern border typically face mistreatment by CBP officials upon arrival. In addition, minors who speak an Indigenous language not only have a harder time understanding everything that is going on, but they also find it especially distressing to advocate for themselves while in CBP custody.

The lack of Indigenous speakers, interpreters and resources at immigration detention facilities not only creates obstacles for minors in telling their stories but can also generate a life-or-death situation for Indigenous children who are ignored when seeking medical or other necessary services.

The Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) language access plans were implemented to provide meaningful access to interpreters

According to Executive Order 13166 signed in 2000, the United States government must “improve access to federally conducted and federally assisted programs and activities for persons who, as a result of national origin, are limited in their English proficiency (LEP)”.54 CBP’s National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (2015) also establishes, under Section 5.1, that extra efforts may be required to ensure an at-risk detainee’s ability to comprehend officer/agent instructions, questions and applicable forms (such as age and/or developmentally appropriate communication, translation/ interpretation services). At-risk detainees include juveniles and unaccompanied minors.

Although these language access policies were implemented, not everyone is receiving these services, especially Indigenous people. The use of interpreters to allow accurate communication between an Indigenous immigrant and any immigration officer, court personnel, attorney, medical staff, etc. is currently lacking. Simply hiring Spanish-speaking interpreters because a large portion of people in the immigration system are from Latin America does not serve the many people from Latin America who do not speak Spanish.

Three Indigenous languages from Guatemala, Mam, K’iche’ and Q’anjob’al, have been added to the list of the 25 most frequently spoken languages in the immigration court system.55 If there is no interpreter in the court, there are over-the-phone interpreter agencies, but there is no guarantee that the interpreter actually speaks the same regional variation of the Indigenous language requested. Sometimes judges deny the use of an interpreter if one is not readily available.56

We have an entire infrastructure set up where the default language is Spanish, but there are thousands of people coming to the southern border who can’t communicate that way — and they basically become invisible.

— Blake Gentry, MPPM (Cherokee), Indigenous Languages Office, Director of AMA Consultants

It is a challenge to navigate the US immigration court systems of the United States if you speak any language other than English or Spanish; think about what it is like in a border facility. Not only is it imperative to have an interpreter in order to accurately explain the reasons for wanting to remain in the United States or explain where your sponsor lives, but think about all the other services that are unattainable for immigrants who need an interpreter while they are in CBP custody. How are their needs being met? How do they know what rights they have? How do they ask for help or express their medical needs?

According to a December 2018 study from the Center for Migration Studies (CMS), Indigenous speakers are less likely to receive medical services than Spanish speakers while in US CBP custody. Five Indigenous children died at border facilities between December 2018 and May 2019.57

One of these was Carlos Hernandez, a 16-year-old Guatemalan boy who was Maya Achi, who arrived at the Texas border in May 2019. Carlos went through an initial medical screening and did not show any signs of illness. Six days later, he was diagnosed with influenza by a nurse practitioner and was later moved to a Border Patrol station to be isolated from others. Carlos was found dead the following morning.58

Jakelin and Felipe were 7 and 8 years old, respectively, when they migrated to the United States, each with a father, in December 2018. They were both from Indigenous Maya communities in Guatemala, and they died a week apart in US Border Patrol custody. DHS sought to blame the children’s fathers by claiming, in part, that they failed to notify CBP officials about their children’s needs for medical care. Jakelin’s father, Caal Cruz, disputes these claims.59

Caal Cruz signed an English-language form saying that his daughter was in good health when they arrived in the United States. Mr. Cruz’s attorneys emphasized that he does not speak English and that he should never had been asked to sign forms in a language he didn’t understand. Jakelin’s father’s first language is Q’eqchi’, an Indigenous Mayan language.60 In an interview with The New York Times, Jakelin’s mother said in Q’eqchi’: “I am living with a deep sadness since I learned of my daughter’s death.”61 Carlos (Maya Achi), Jakelin (Maya Q’eqchi’), Felipe (Maya Chuj), Wilmer, and Juan (Maya Ch’orti’)62 are five Indigenous children who died in US custody between December 2018 and May 2019. Their deaths should, at a minimum, emphasize the need for interpreters who can accurately provide real-time interpretation for people who are most at risk. The need for US immigration agencies to be more proactive with the use of interpreter services should be considered a priority during screenings for health, asylum claims, or any other request for protection.

Indigenous minors are more than just a demographic, a statistic or a number. It’s essential that all those who work with Indigenous unaccompanied children in detention understand the unique concerns of people of Indigenous descent.

We must also learn to recognize Indigenous children’s unique linguistic needs at our borders, in our legal services, and in our courts.

Unsanitary Conditions: Lack of Basic Necessities at Border Detention Facilities

By Lia Mora

It’s within everybody’s common understanding that if you don’t have a toothbrush, if you don’t have soap, if you don’t have a blanket, it’s not safe and sanitary.

— Senior US Circuit Judge A. Wallace Tashima, June 201963

The Flores Settlement Agreement, which governs the treatment of children in Department of Homeland Security (DHS) custody, states as follows: Paragraph 12A of the Agreement provides that children who enter the United States as unaccompanied children shall be held in “safe and sanitary” facilities following their arrest. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities must “provide access to toilets and sinks, drinking water and food as appropriate… [and] adequate temperature control and ventilation.”64 The conditions at these facilities must also be “consistent with the INS’s concern for the particular vulnerability of minors.”65 Despite the requirements of the Flores agreement, many of the 9,417 minors who we met with in 2019 had complaints regarding safety and sanitation practices in detention facilities.

La Hielera and La Perrera

When immigrants encounter CBP along the Southwest border, they are brought to holding cells for processing. The 2009 CBP Security Policy and Procedures Handbook describes the holding cells as small concrete rooms, “not designed for sleeping.”66

These facilities are often referred to as hieleras and perreras by immigrants and border security agents. The hielera is a facility described by immigrants as a frigid and crowded holding cell. Perrera translates to dog kennel and is described by immigrants as a room similar to a large warehouse, full of cages with chain-link barriers. Adults and children may be divided up in these cages by age or country of origin.

Both the Flores settlement and CBP’s National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS) set requirements on the treatment of unaccompanied minors in these holding cells, such as “toilets and sinks; professional cleaning and sanitizing at least once per day; drinking fountains or clean drinking water along with clean drinking cups; adequate temperature control and ventilation; and clean bedding;”67 plus attempts to grant minors access to “showers, soap, and a clean towel” when they are nearing 48 hours in detention.68

However, as the testimonials below demonstrate, most of the children interviewed were held in deplorable conditions in violation of the standards set out by the Flores settlement and CBP’s own policy.

Sleeping Conditions

Contrary to the requirements in the Flores agreement, the living and sleeping conditions in detention centers were the subject of complaints from children and teens. More than 64% of minors AI Justice interviewed had been detained in facilities such as a hielera or perrera and complained about the sleeping conditions in these facilities.

Many children said they were given a piece of aluminum as a blanket and a thin mattress to sleep on. These aluminum blankets did not provide enough warmth for the very low temperatures of the hielera. Segundo, a 17-year-old boy from Ecuador, explained, “The facility was cold every night. Sometimes there would be so many people that there would be no space to sleep lying down; I would have to sit. I slept on the floor every night with an aluminum blanket.”

Claudia, who was 15 years old at the time of her detention in the hielera, said, “They didn’t let us sleep because they would call our names throughout the night. They didn’t give us mattresses, only aluminum blankets, but I saw that if we covered ourselves with them, the officers would pull them off other girls.”

Underage mothers and their babies were not accommodated. Leticia, who was detained for 24 days in the perrera with her 3-year-old daughter Bertola, had an even more disturbing experience. Leticia was placed in a cell with about 300 other girls. She says that she was sometimes provided with an aluminum blanket and a thin mattress, which were taken away between 5 a.m. and 9 p.m. Leticia said: “If someone dropped some milk, everyone would be punished by not being able to sleep with mattresses for the night. Twice, me and my daughter were kicked by officers to be woken up.”

Lack of Water and Food

About 40% of unaccompanied minors who were interviewed by AI Justice complained about the lack of food and water in border detention centers. The 2008 CBP Memo regarding Hold Rooms and Short-Term Custody requires officials to provide juveniles who are detained for longer than eight hours with regularly scheduled hot meals, and to provide snacks and milk upon request for the youngest detainees and pregnant women.69 Unfortunately, detained minors said CBP often failed to adhere to this policy.

For example, Skarleth, a 10-year-old girl from Honduras, mentioned during her interview, “There were pieces of ice on the sandwich they gave me in the hielera. In the perrera, they just gave us a dry slice of bread and a slice of bologna.”

Santos, a 16-year-old girl, was detained in the hielera for one day and the perrera for nine days. Santos explained the difficulties that she went through: “They only gave us food whenever they decided to. I went one day without eating because they did not give us food.”

Felipa, from Guatemala, was 17 at the time of her apprehension and spent five days in the perrera. She said during her interview: “They gave us water, but it tasted like Clorox. I got sick because of the water that I was drinking. I asked the guards if I could see a doctor. They said that if I went to medical, I would have to stay detained for longer.”

Lack of Dental Hygiene and Showers

Lack of ability to practice dental hygiene was another issue. Maynor, a 15-year-old boy from Honduras, was detained for 29 days in the hielera and two days in the perrera. He said, “We could only shower every three days. We were only allowed to brush our teeth when we showered.” Other minors also complained about not being able to brush their teeth.

Edwin, who is 17 and was detained for longer than 72 hours, said during his interview with an AI Justice shelter advocate, “In the hielera, they didn’t let me shower. I was only able to shower when I got to Georgia. I wasn’t able to brush my teeth until I got to Georgia, either.” Walter, 14 at the time of his apprehension, was detained for nine days and was only able to brush his teeth and shower once.

Toilets and Portable Bathrooms

Lacking privacy and a safe space to use the shower and toilet would be terrifying and inhumane to many of us. Unfortunately, some children were not allowed to use the bathroom as needed while at these border detention facilities. Rony, a 16-year-old boy from Guatemala, told the AI Justice team, “There were days that the guards did not give us access to the bathroom. I had to hold it for hours.” Jose, who was detained in the perrera for 10 days, shared a similar story. He said during his initial interview, “One day the officers did not allow us to go to the restroom for almost two hours. Some of the minors were holding it so long, they peed in some empty bottles.”

Girls didn’t have it any easier. Denia, who was 17 at the time of her detention, explained that she was alone in a small room with a small window. She stated, “The bathroom was not private at all, because I could be seen going to the bathroom if someone looked in the window.”

Marielena, 16, said she spent four days in the hielera and noticed cameras in the bathroom. When she asked the guards about them, they replied, “The minors are used to it.” Emiliana and Roxana were detained for longer than three days. They both had to avoid washing their bodies because there were cameras in the showers.

2019 Conditions Ruling

On June 26, 2019, a group of lawyers who toured the holding facilities in El Paso and Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sectors filed for relief for children held in these facilities, citing the blatant violations of the 1997 Flores settlement order and the June 17, 2017, Flores v. Sessions order.70 The lawsuit included more than 60 declarations, including from children who were detained at these facilities, describing many of the same inhumane conditions described by the children interviewed by AI Justice.

Shockingly, the attorney representing the Department of Justice argued that the government is not required to provide soap, toothbrushes, towels or dry clothing to children, and that children can sleep on concrete floors in frigid, overcrowded cells to meet the requirements of “safe and sanitary” under the Flores agreement since the agreement did not specifically state that these things were required.71 Ultimately, the District Court concluded in its ruling, “Assuring that children eat enough edible food, drink clean water, are housed in hygienic facilities with sanitary bathrooms, have soap and toothpaste, and are not sleep-deprived are without doubt essential to the children’s safety.”

Where’s the Baby Food? The Lack of Age-Appropriate Food and Its Consequences

By Sofia Aumann

Some of the unaccompanied minors that cross the border into the United States have children of their own. The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP)’s October 2015 National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search (TEDS) have policies to address the needs of this population, which are referred to as an “at-risk” population.72

We spoke to 11 teens who were placed in CBP detention facilities with their babies. Of the 11, only four reported receiving age-appropriate food for their infants. Instead, their babies were given the same food the older children received, which consisted of burritos, for example, which were often frozen or not cooked properly. This resulted in some of the babies vomiting or having diarrhea.

One mother, L.E.R.R., recalled, “My daughter was given the same food I was given, but she didn’t like it. She was still drinking from a bottle before detention, and they would not give her any. She was denied milk and formula because she was 3 years old. She went days without eating because she didn’t like the burrito or other food given to us.” M.E.R., another mother, also reported having been denied baby food for her child. She said: “[The] officer inside the detention center would not give my daughter formula [because] she was too old. My daughter was 3. . . . The first day, she was given a bottle. . . . By the morning, the officer told me my daughter was too old. She cried that she wanted her bottle. She was then given a burrito with egg and juice and chips.”

The standards do not specify what ages qualify for what age-appropriate foods, and this lack of clarity likely gives the officers the broad discretion to decide, against the mother’s recommendation, what their babies should eat. Exactly when babies should eat which solid foods, and when they should give up their bottles, depends on a number of developmental factors, specific to each child, according to medical experts. CBP officers should not, therefore, be deciding which child is too old to receive baby food or a bottle without consulting a medical professional.

Four of the seven mothers who reported not having any ageappropriate food for their babies also reported that their children became physically sick from the food they were forced to eat. “The food was sometimes cold,” recalled R.M.F.U., whose child was less a year old when they crossed the border. She explained, “I had access to diapers, but they didn’t give me special baby food for my son. I had to feed him the same food they gave me, and he would throw up from it. They gave him medicine for the vomiting.” Another mother said, “Sometimes the rice or the beans in the burrito are not cooked. They’ll be half cooked. . . . One time, the food affected me. I did not like it but was hungry, so I ate it and felt bad and I threw up. My baby too, I gave it to her, and she got diarrhea. No special food for the baby.”

Three of the 11 mothers reported that they had crossed the border with food, as well as other supplies, for their babies. However, immigration officers took their belongings when they were apprehended. One mother, M.E.R., explained, “I had carried clothes and a bottle with formula for my daughter and they made me throw them out.

Many of these mothers requested specific food and snacks from the immigration officers for their babies but were often denied. For example, R.M.F.U. told us, “If I asked for things, like water or another cookie for my baby, they wouldn’t give me what I asked for. They would tell me I had to wait. . . . Sometimes when I asked them for things, they would say they didn’t have it or couldn’t get it, but I knew they had access to it and just didn’t want to get it for me.” Another mother, M.E.P.L., said she asked a CBP officer for baby food for her year-old child. “I asked if she could have baby food and they said ‘no’. They gave other kids yogurts but not to my baby.”

Although CBP standards award unaccompanied minors and their babies certain rights when it comes to the food they receive in detention, the language is extremely vague. There are no specifics as to what ages require what foods. CBP officers should not be given broad discretion to decide what babies or toddlers can receive which foods. A wrong decision can have a serious impact on a baby’s health. What we have repeatedly seen is that few young mothers were listened to when they expressed to CBP that their child had unmet dietary needs. These practices have resulted in sickness and unnecessary discomfort for the babies and their mothers.

When the Most Vulnerable are the Least Protected: Illness and Medical Care in Custody

By Maria Valentina Eman

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

— Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights73

A mother’s instinct when seeing her child unwell is to immediately help. But what if you are being held in unsanitary conditions? This is the reality for many young mothers in CBP custody at the US-Mexico border. The Flores Settlement Agreement guarantees that children shall be held in “facilities that are safe and sanitary.”

During our interview process, we discovered that numerous children from the ages of just a few months to 4 years old became ill when detained by CBP and did not have access to proper medical care. Young mothers and their small children reported being held with others who reported illnesses from a fever to dehydration.

The lack of appropriate food, warm bedding, clean clothing, plus limited access to hygiene products and places to bathe, does not allow these young children or their mothers to recover from illness. Of our 11 interviewed young mothers, eight reported their children became ill at a border facility. They confirmed they were not sick prior to entering CBP custody. They reported that they were denied medical attention unless they had a fever. Paula told us that her 2-year-old daughter was never provided with any age-appropriate food, and because of this, couldn’t eat. During their 16-day stay, they were seen by a medical professional only when Paula’s baby became very ill and emaciated and had to be taken to the hospital. Paula told us that her daughter’s eyes were so red and swollen due to the never-ending bright lights that she could no longer open her eyes, and that the poor air quality inside the facility prevented her daughter from being able to breathe. Paula’s daughter’s “Verification of Release,” which has a picture taken at the time the child is placed in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), shows her swollen red eye. Paula and her baby were never taken to a medical facility at the border facility or placed in medical isolation; they were only moved to an isolated cell where many other sick babies and their mothers were being held.

When I went to the doctor, [at the CBP facility] they told me I did not care about my daughter’s health. I told them I did but there was nothing I could do because I would tell people at the facility that she was sick, and they would say she was fine. They only gave me acetaminophen.

— Paula

Paula’s case was not unique. It was widely reported that mothers and their babies were taken to a doctor only when they had a fever. Even after she reported her child’s fever, another young mother named Heidi was told she had to wait 40 minutes because a shift change was due. Once Heidi’s baby was finally seen, the doctor told her that her child had a cold and was dehydrated. The baby was given medicine and sent back to the cell with its mother. They were never isolated nor permitted to stay in the medical area. Another young mother was denied extra blankets and was never given medication for her asthmatic baby, who was being held in a frigid facility. Most of the mothers who were put in isolation because of their babies’ fevers were packed into cells with other mothers and sick babies. As if the struggle to receive medical attention were not enough, one young mother, Kenia, reported being shamed by CBP officers.

They told the minors who were mothers that they were less of a priority. They shamed us.

— Kenia

The Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) states that an unaccompanied minor needs to be transferred from CBP custody to ORR within 72 hours of when CBP determines the child is unaccompanied (Memorandum, 2009).74 Every mother we spoke to reported being in CBP custody for four or more days, with some saying they were detained as long as 20 days at a border facility. CBP facilities are designed for short-term detention, not to hold people longer than 72 hours. Exceeding the 72-hour statutory limit is problematic, given the deplorable and inhumane conditions of these facilities, which can often lead to children becoming sick and left without access to medical assistance. On December 29, 2019, CBP released a new directive (CBP Directive No. 2210-004, 2019) outlining provisions for better medical support for those detained at the US-Mexico border.75 CBP officers must provide medical assessments, at a minimum, for children under 12 or with a mandatory referral. If there is no medical professional on site, children can be referred to available health care providers.

There is no reason not to provide clean and safe areas for detained children and teens, let alone medical care until someone is seriously ill. Hopefully, this new directive will keep young mothers and their children safe, as well as safeguard all detained migrants at the border.

Juan’s Story: A Minor’s 58 Perilous Days in Adult Detention

By Janette Vargas

Name: Juan. Age: 17

In spring 2019, Nicaraguan youth gathered, waving their blue and white flags against the repressive state.76 Juan was among those advocates. “I participated in a protest for Azul y Blanco against our current government. It was a passive protest on our end, but a lot of people were killed by the military,” Juan said. “The military is threatening people.” The Nicaraguan military threatened Juan’s family, including the then 16-year-old. Thousands of Nicaraguans have fled their country because of increased violence and political unrest.77 Juan is one of them.

Near the summer of 2019, Juan fled north to the United States. Shortly after crossing the Texas border, Juan was apprehended by US Customs and Border Protection (CBP). “Immigration thought that I was older than 18, even though I showed them my birth certificate. They held [me] for three days without food, water or sleep while they investigated.” When Juan questioned agents regarding his treatment, he was handcuffed. “I was shackled. . . . [I] told them that I was not lying.” After three days without food, water, or sleep, Juan decided to tell them what they wanted to hear. “They did not believe me, so I just told them I was 19 years old. That is when they finally gave me food, water and a place to sleep.”

After four days of being held in a detention cell with adult men, Juan was served with a Notice to Appear (NTA) with an incorrect date of birth listed on the official document. The date of birth wrongly listed Juan as a 19-year-old.

The first place did not feed me, give me water or let me sleep for three days because they didn’t believe me or my birth certificate… I was a minor. In the hielera they didn’t let me shower. I only was able to shower when I got to [the adult detention center]. I was not able to brush my teeth.

— Juan, age 17

Juan was then taken to a hielera, a detention facility known for its frigid temperatures. The 16-year-old was detained in a cell with grown men in frigid temperatures for four more days before being transferred to an adult detention center. “It [the hielera] was very cold and awful. I was held with adults. After the four days, I was sent to another adult detention center. I was there for 50 days.”

Juan remembers the mistreatment by border agents. “The first place did not feed me, give me water or let me sleep for three days because they didn’t believe me or my birth certificate. . . I was a minor. In the hielera they didn’t let me shower. I only was able to shower when I got to [the adult detention center]. I was not able to brush my teeth.»

It took Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) 58 days to notify the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) and correctly identify Juan as a minor. After 50 days in an adult detention center, Juan was finally transferred to a children’s shelter. Juan had to wait an additional 102 days in two separate ORR facilities for unaccompanied children before being able to reunite with a family member in the United States.

When asked if he was afraid to return home, Juan responded, “Yes. . . . I am not sure what would happen. Maybe the government/military would kill me or harm me.”

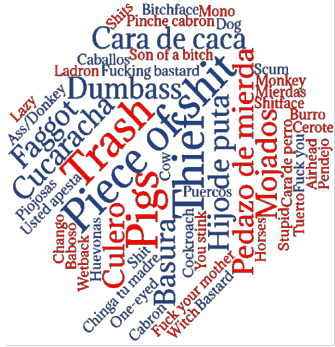

Detention as Punishment: 72+ Hours of Physical and Verbal Abuse

By Genesis Barrios and Rosario Paz

There are no cameras here. No one is going to see us hitting you. We are the law here.

— Border Patrol officer to a 17-year-old boy from Mexico

Countless children and teens screened by AI Justice reported excessive force and punishment at the hands of officers while detained at the border. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP)’s own National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention and Search (TEDS) state that “CBP employees will perform their duties in a non-discriminatory manner, with respect to all forms of protected status under federal law, regulation, Executive Order, or policy, with full respect for individual rights including equal protection under the law, due process, freedom of speech, and religion, freedom from excessive force, and freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures”87 (emphasis added).

CBP officers may be the first individuals a migrant child encounters upon arriving in the United States. This encounter comes after children have made a long, dangerous journey, often after fleeing abuse in their home countries. Children come to the United States expecting to be safe. Instead, they face abuse by the first people they encounter.

The mistreatment of immigrant children by officers, as well as the inhumane conditions of the facilities in which they are held, was first decried by legal advocates and activist groups in the 1980s through a series of lawsuits.79 The Flores Settlement Agreement, a landmark resolution establishing standards for the care and detention of minors, was “carefully crafted after over a decade of litigation to help ensure that the best interest of the child is a priority during government care of . . . unaccompanied children.”80

What we saw throughout our thousands of conversations with children and teens in 2019 was a complete disregard for these standards and an abandonment of the safeguards in place for a population as vulnerable as children. Of the 9,417 unaccompanied immigrant children we interviewed, 147 children reported physical abuse by CBP officers and 895 children (nearly 10%) reported verbal abuse. Children who did not experience abuse firsthand saw it happen to others. It is possible that even more children were subjected to or witnessed abuse in CBP custody but chose not to disclose this. CBP has published standards about how its officers should deal with vulnerable populations, including children. While officers are required to undergo training on these rules, numerous reports by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) starting in 2010 have found that CBP is unable to say exactly how many officers have received training.

Apprehension: The First Encounter

When Gabriel, a 17-year-old boy from Guatemala, entered the United States with his brother, CBP officers stopped both boys, threw them to the ground, and handcuffed them. Gabriel explains that, when he lifted his head to avoid having his face on the ground, an officer punched him in the face. Gabriel’s brother tried to move toward Gabriel, who remained restrained on the ground. In response, an officer punched Gabriel’s brother in the face and pulled his shirt so hard that it ripped.

Gabriel’s brother was left with marks on his chest and arm. Gabriel and his brother were taken to a holding cell in a CBP station and then to another location. At the border facility, an officer grabbed Gabriel’s face and demanded that he look at her. She asked, “Did you really try to hurt my officers?”

Gabriel did not respond. The officer said she was going to instruct her officers to take Gabriel to a location where they could do whatever they wanted to him and his brother. Officers continued to threaten and harass Gabriel until he was transferred from CBP custody.

Twenty other children shared similar accounts of physical abuse, use of excessive force, or inappropriate use of restraints by CBP officers as they were being apprehended.

Osvin, a 17-year-old from Guatemala, crossed the desert with seven other migrants. They had walked for 16 hours when CBP officers spotted them. The officers chased Osvin on their ATV, hitting him with their vehicle and knocking the wind out of him.” Osvin stated he felt like he was “going to die.” He was handcuffed until they arrived at a detention facility. He did not receive any medical attention.

Elena, a 17-year-old mother, traveled from Honduras with her 2-year-old son and a large group of other migrants. When she and the others were trying to get into a car, Elena didn’t fit. Since the others were going to leave her, Elena requested that they leave her son with her, but they took him instead. When five CBP officers came afterward, Elena told them what happened. She explains how the officers responded:

“I was really scared because of my son . . .all they said was that I was not going to see my son again.»

When she was picked up, she was handcuffed for 15 to 20 minutes. The restraints were taken off when she got into the patrol car.

Eight other children reported that, when they were apprehended, they were thrown to the ground “hard” or with lots of force. CBP officers grabbed children and pulled them to the ground or pushed them so that they would fall. Four of these children said that, after they had been thrown to the ground, CBP officers either placed a knee on their backs or chests or shackled them.

A 17-year-old from Guatemala named Marcos said that, when he was apprehended, CBP officers put Marcos’ shoes in his mouth, took off his jacket, shackled him, and then pushed him against the patrol car.

When Santiago, another Guatemalan boy, was apprehended, CBP officers told him, “Te agarramos, putito.” (“We got you, little faggot.”) They shackled him and pushed him to the ground, where Santiago lay for 15 minutes: “I felt bad. Uncomfortable. I had never been shackled before.” While he was on the ground, officers asked Santiago about his age. After Santiago told them he was 16, officers asked for his birth certificate and lifted him to a sitting position. While he was seated, with his hands restrained behind his back, Santiago felt an officer step on his fingers:

“I told him he was hurting me.”

As Santiago recalled the incident, he was unsure about the official’s intentions: “I don’t know if it was by accident or if he was trying to hurt me.”81

Even when children turn themselves in, there is no guarantee they will not be abused. Alvaro, a 17-year old boy from Guatemala, explained that when he crossed the border, he turned himself in and showed no violence, yet he was restrained with excessive force:

“I put my hands up, but an immigration official put [his] foot in front of me, [elbowed] me and pushed me so I could fall to the ground. Then, he shackled me.”

Javier, a Guatemalan 17-year-old, recalled a CBP officer who grabbed the strings of his sweater, tightened the strings to cut them with a knife, and nearly strangled him. A second CBP officer then grabbed the back of Javier’s sweater, pushed him, and told him to pick up the garbage in the patrol car. Melvin, a Honduran 17-year-old, was hit with a stick by a CBP officer who caught him at the border. He was thrown in the car and was hit again with a stick on the chest. A 16-year-old Guatemalan boy named Sergio remembered walking through a big net and being physically assaulted:

«A CBP officer put a gun to his head, asked him for his sweater and asked him to take off his shoelaces and belt, even though he did not have a belt.»

Lack of language access was also an issue. Ranjit, a 17-year-old boy from India who speaks only Punjabi and a limited amount of English, recalled that when he crossed the border near Mexicali, he saw uniformed officers in a car. “The officer was yelling at me. I didn’t understand what he was saying.” The officer grabbed Ranjit by the neck and put him in the car. Another 17-year-old, an Indigenous Kaqchikel boy from Guatemala named Edwin, said he was hit in the chest after he turned himself in:

“When I turned myself in, they were talking in English and they wanted me to have my hands out of my pockets, but I didn’t understand. That’s when they hit me in the chest.”

There is no justification for a CBP officer to hit, grab, push, restrain or throw to the ground any child. Of additional concern is that the abuse is sometimes a result of children not understanding instructions because of a language barrier.82 When CBP officers violate these basic standards and abuse children, children don’t understand what happened or why, making them less likely to report incidents of abuse.

Detention: A Long Traumatic Stay

Unfortunately, both physical and verbal abuse often continue in detention. Children we interviewed reported being “treated like animals” or “like garbage.” Many reported abuse by officers while in CBP detention facilities, making it a long, traumatic stay for these children, especially for children who were detained longer than 72 hours.

The worst days of my life were in the perrera (dog kennel).

— Rudy, a 16-year-old boy from Honduras

Excessive Force by Officers

Incidents where small matters quickly escalated into something beyond the scale of the original issue were frequently reported, and excessive force was often used by CBP officers.

Juliana, a 17-year-old Guatemalan girl, was carrying her phone and was asked by a male officer what she had against her chest. When she was about to hand it over, a female officer was called over and Juliana was asked again what she had against her chest. Juliana tried taking out her phone, and the female officer called her a liar. The male officer grabbed her arms, put them behind her back, pushed her against the wall, and proceeded to bang her head on the wall. Juliana was crying and visibly upset when relating this incident and said she “felt like a criminal.”

In another incident, a 14-year-old Salvadoran girl, Rosa, experienced abusive treatment by an officer over an accidental touch. Rosa was being transferred to a shelter for unaccompanied minors when she noticed a friend had left her backpack in their cell. Rosa returned to the cell to grab the backpack and walked behind a male guard. When the guard moved his arm back, he touched Rosa, then insisted she had hit him intentionally, she said. The guard started screaming at her, grabbing her very hard by the arm and throwing her onto the floor.

Neither girl had a weapon or anything that resembled one. Neither had violated any rule yet faced excessive force without any explanation.83 These girls did not pose any “foreseeable risk of injury” to the officers, nor did they resist or make any attempt to escape.84

Excessive force was often used to bully and intimidate. One 17-year-old boy from El Salvador named Henry says three officers grabbed him and surrounded him, then told him that he wasn’t as old as he claimed. They interrogated Henry for 15 to 20 minutes before grabbing him by his pants and pulling them up. Henry says they further intimidated him by telling him he would go to jail for lying. Another 17-year-old boy from Mexico named Antonio says some teens with him had gotten into a fight in which he was not involved. Nonetheless, Antonio says, all of them were handcuffed for three hours. The officers showed Antonio their batons and threatened to hit him, saying, “There are no cameras here. No one is going to see us hitting you. We are the law here.”

Such words reveal an underlying belief on the part of some officers that they are free to act as they see fit, with no limitations. These actions are a direct violation of the requirements established by the original Flores agreement and its subsequent expansions.

Verbal Abuse

An alarming number of children told us about “ruthless” officers who subjected them to verbal abuse.

Several children said CBP officers cursed at them, laughed at them and made fun of them, insulting them in English, speaking harshly to them while going over the rules, yelling and whistling at the girls, or yelling at them for looking out the windows of their cells, or for no identifiable reason. As Dilan, a 17-year-old Honduran, explains it, “They’d yell at you when you were lying down. You couldn’t stand [either] — they would scream at you and tell you to sit down.”

Five children reported being screamed at or insulted for making normal, basic requests, such as asking to use the bathroom. One asked a guard for a mylar blanket and was told he wasn’t a man. Another asked for a blanket and was told she and the others were good for nothing and came into the country to ruin it. Another child recalled being insulted by an officer who only let them have one bedsheet and told them:

“You’re not in your house. You don’t have rights to anything.»