October 2, 2018

By: Tim Henderson

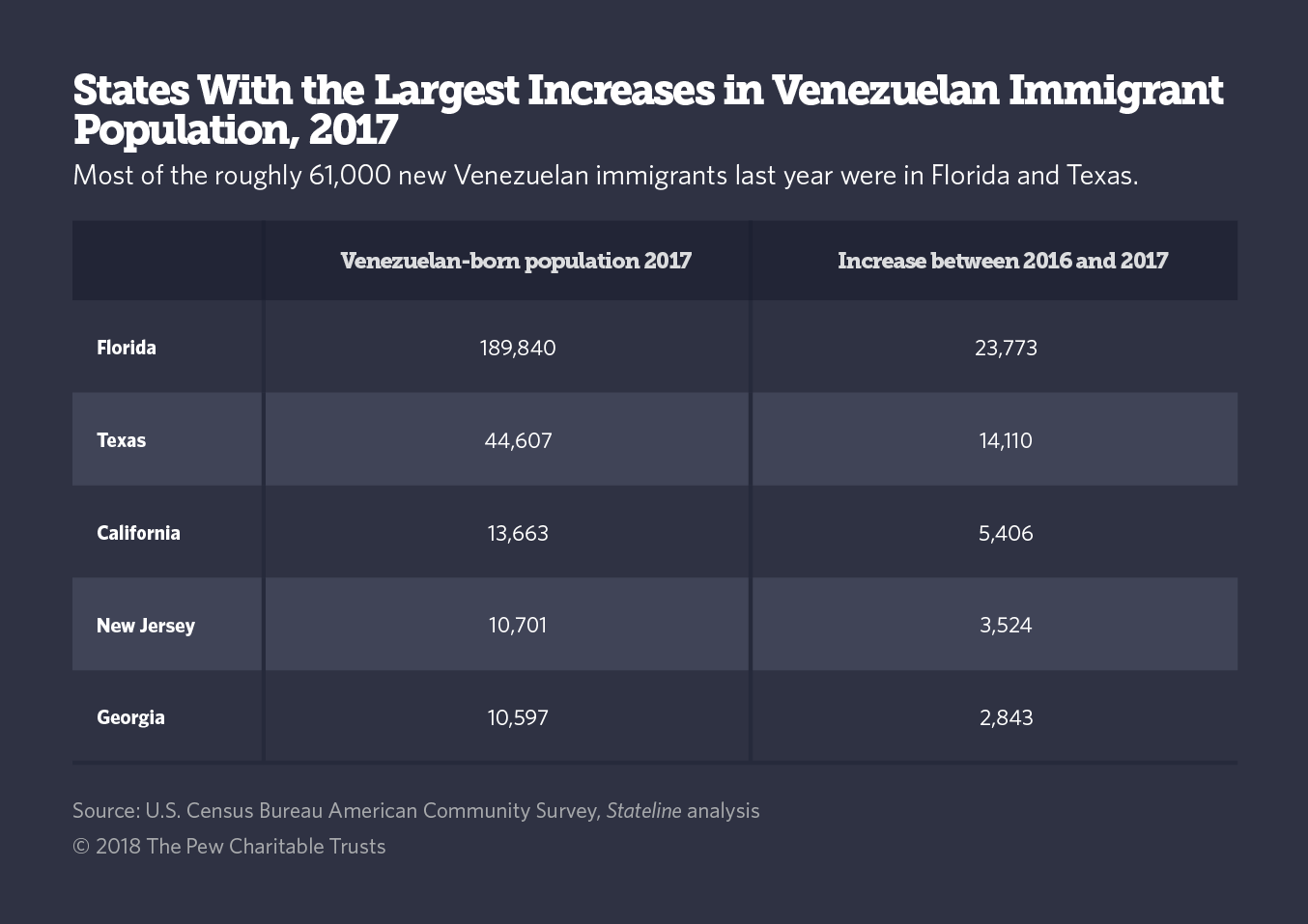

Florida, Texas, California, New Jersey and Georgia got the lion’s share of new Venezuelans, and earlier waves of Venezuelan immigrants are organizing to help them. Nationally the Venezuelan immigrant population has nearly doubled since 2010 to more than 350,000, according to census figures.Although the Trump administration has criticized the Venezuelan regime and expressed support for its citizens, the administration has so far refused to grant legal status to immigrants fleeing to Florida, Texas and other states.

A petition filed last year by the Venezuelan American National Bar Association for temporary protected status, a legal status for immigrants from countries in crisis, has not yet been acted on by the Department of Homeland Security. Human Rights Watch, a nonprofit, also has called for temporary legal status for Venezuelans anywhere in the Americas during the crisis.

“There really hasn’t been a coordinated response,” said Andrew Selee, president of the Migration Policy Institute. “It came up so suddenly that it wasn’t really on the political radar until recently.” The Trump administration has provided about $100 million to house refugees in countries neighboring Venezuela, he added.

“In Venezuela there is nothing — no money, no medicine, almost no food, no public transportation — the only way to leave is to walk.”

Tomas Paez, sociologist CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF VENEZUELA

It is rare for the United States to grant blanket legal status for those escaping a regime, but it was granted for Cubans until 2017. While some immigrants fleeing conflict or natural disasters have been granted temporary legal status, the Trump administration has been phasing that out as part of its crackdown on immigration.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which makes the final decision on protected status, said the department has “no announcement to make at this time” about legal status for Venezuelans.

Venezuela is in “a downward spiral with no end in sight,” the United Nations said in a June report. A mismanaged state-controlled economy has made food and health care unavailable to many people, and dissidents have been jailed and tortured.

Shift in Policy Follows Dramatic Rise in Cuban Immigration

President Nicolas Maduro has blamed 2017 U.S. sanctions for the economic crisis, though the UN report, by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, said the crisis had been building for years. Experts blame the crisis on hyperinflation, decisions made by the socialist party in power since 1999, and the nation’s dependence on selling oil.

Venezuelans who can afford to make the journey to the United States now often are educated professionals but may take low-level jobs to survive, using tourist visas and asylum applications as a short respite while they consider their next move.

“These are people who didn’t qualify for anything else, and they’re desperate to get out,” said Adriana Kostencki, president of the Venezuelan American Bar Association in Florida.

In South Florida, pro-bono attorneys sometimes see fellow lawyers from Venezuela among those in detention centers awaiting deportation, said Jessica Schneider, director of the detention program at the Florida-based Americans for Immigrant Justice law firm.

Venezuelans have come under more scrutiny lately, she said, and U.S. officials may detain those who arrive with a tourist visa if inspectors suspect that they intend to stay rather than visit. That might involve searching a cellphone for posts and texts about moving to the United States.

“They will absolutely search your phone and go through your luggage to see if there’s, maybe, a pile of resumes,” Schneider said. Venezuelans who are denied entry can be detained while they wait for asylum hearings or deportation, she added. The number of Venezuelans deported last year increased from 182 to 248.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection did not answer requests for comment.

More Venezuelans are applying for asylum than any other country, federal statistics show. But they don’t have much chance of getting it, said Kostencki.

“You can go to a judge and say you’re afraid to go back to Venezuela, but that doesn’t mean you’re entitled to asylum,” said Kostencki, noting that asylum requires evidence a particular group is being threatened. Kostencki was part of an earlier wave of Venezuelans who came to the United States for college and stayed with a high-skill visa that can lead to legal status.

When Venezuela was more prosperous, middle-class immigrants could come legally as workers for multinational oil companies under visas granted to experts in their field or get legal status as job-creating investors.

Any influx based on tourist visas may be coming to an end now. In 2017, the number of tourist visas issued to Venezuelans dropped off to less than 57,000 after reaching almost 240,000 in 2015.

That could be because of increased scrutiny of tourist applications by the United States, delays in getting Venezuelan passports as the crisis deepens, or Venezuelans may simply be running out of money.

Tomas Paez, a sociologist at the Central University of Venezuela who studies the country’s migration patterns, said few in the country have $100 for a tourist visa application, let alone $600 for a plane ticket, when even a full professor like himself earns the equivalent of a dollar a month because of inflation.

“The only way they can do it is if somebody on the outside sends the money, or somebody had the money saved up from their work,” Paez said. “In Venezuela there is nothing — no money, no medicine, almost no food, no public transportation — the only way to leave is to walk.”

People are fleeing to surrounding countries at record rates. Luisa Feline Freier, an assistant professor of social sciences in Peru, called it “the fastest-escalating displacement of peopleacross borders in Latin American history” in a recent article.

The influx from Venezuela to the United States comes even as the number of Mexican immigrants living here dropped more last year than at any point in the past decade because of crackdowns as well as opportunity south of the border.

The Trump administration and some states have made a point of criticizing the leftist Maduro regime in Venezuela. President Donald Trump told reporters last month that he wants “to see Venezuela straightened out,” and in June Vice President Mike Pence met with Venezuelans in Brazil to say “we will keep standing with you until democracy is restored in Venezuela.”

Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida has even floated the idea of invading Venezuela, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said he’s preparing “a series of actions” against Maduro’s socialist government.

Connecticut called for a divestment of $30 million in state investments, mostly bonds, tied to Venezuela, in a bill that passed the House this year, and is awaiting a state Senate vote, saying the investments “enable Venezuela’s corruption and the impoverishment of the Venezuelan people.” The Connecticut Petroleum Council objected to the bill, saying it was “aimed squarely at the oil and gas industry” in the state, which has investments in Venezuela.

Florida enacted a Venezuelan divestment law in March, barring state investment in companies doing business with Venezuela, and the Illinois House last year passed a resolution protesting human rights abuses there.

Meanwhile, Venezuelans who are longtime U.S. residents are trying to help.

Venezuelans are the most educated Latin American group in the United States — more than half of adults have college degrees, compared with fewer than 10 percent for those from Mexico and Central American countries, according to a Stateline analysis of American Community Survey data from the University of Minnesota.

Venezuelan communities in the United States are organizing to help the newcomers as well as those left behind in Venezuela without enough food or medicine. Rafael Gottenger, a plastic surgeon in South Miami, Florida, volunteers for the Venezuelan American Medical Association to help doctors and patients in Venezuela with medicine that can’t be purchased there because of shortages.

“There’s a lot of people helping people going on,” Gottenger said.

Franklin Rivas, a Venezuela-born executive at an airplane parts company near Miami, said he looks for employees from the new immigrant pool, and tries to help his parents and other relatives back home.

“They haven’t had things like chicken in years,” Rivas said. “My dad needs heart medication for his blood pressure, and there isn’t any there, so I have to go around and try to find somebody who can prescribe it, so I can send it.”

Read it via Stateline here.