The Family Expedited Removal Management Program (FERM): A Three-Month Assessment

Highlighting the Need for a More Family-Centered Approach

Published September 7, 2023

Prepared by: Cindy S. Woods, National Policy Counsel, Americans for Immigrant Justice

Click here to download the report (PDF)

Executive Summary

In the lead up to the end of COVID-era entry restrictions at the U.S. southern border, the Biden Administration announced a number of new policies aimed at deterring migrants from traveling to the United States outside of a limited number of pathways. The centerpiece of the Administration’s new border strategy is a new asylum ban, which establishes that any individual who enters the U.S. from Mexico without documents sufficient for lawful admission is ineligible to seek asylum. Only individuals or families who schedule an appointment for processing at a port of entry (POE) through a glitchy mobile app (CBP One), who applied for and were denied asylum in another country through which they travelled, or who can show exceptionally compelling circumstances for entering without an appointment are eligible to seek asylum. This asylum ban has been found unlawful by a federal judge, although it is still in effect as of this report’s publication due to a stay pending appeal of that decision.

Alongside the asylum ban, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) sought to “increas[e] and enhanc[e] the use of expedited removal”—the summary removal of an individual without further process unless that individual expresses a fear of persecution or torture if returned to their country of origin. Asylum seekers placed in expedited removal are referred to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) for a Credible Fear Interview (CFI), where an asylum officer (AO) decides whether they have shown a “significant possibility” of prevailing on a claim for asylum, withholding of removal, or relief under the Convention Against Torture (CAT). Under the asylum ban, individuals who enter without a CBP One appointment and who cannot establish an exception are ineligible for asylum during their CFI and held to a heightened standard, under which they must establish a reasonable possibility of eligibility for withholding of removal and CAT relief. Only individuals who establish a credible fear claim are permitted to submit an application for asylum and other protections in full removal proceedings under Section 240 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) for consideration by the Immigration Judge (IJ). Individuals who do not establish a credible fear are promptly removed from the United States.

Historically, individuals placed in expedited removal are detained in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody pending their CFI. The Biden Administration announced two new policies to increase its use of expedited removal: (1) conducting CFIs in Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) custody; and (2) conducting CFIs for family units outside of detention—a program referred to as Family Expedited Removal Management (FERM).

The Biden Administration’s use of expedited removal as a punitive measure against asylum seekers who enter without a CBP One appointment exacerbates long-standing criticism by advocates that expedited removal summarily denies access to protection to bona fide asylum seekers. Expedited removal hinges on an individual’s ability to testify to their fears of past and future harm during a high-stakes interview with an AO that includes few procedural protections. Although the AO’s decision may be reviewed by an IJ during a brief hearing, that decision is not appealable to the Board of Immigration Appeals or federal courts. CFIs have historically taken place in remote ICE facilities, where access to counsel is difficult and representation rates are drastically low. The expansion of CFIs to individuals in CBP custody is exceptionally deleterious to the due process rights of asylum seekers as access to counsel is essentially completely denied.

Under the FERM process, family units are put into expedited removal, placed under electronic surveillance—including a GPS-enabled ankle monitor, a curfew, and electronic monitoring via a SmartLink device—and released from CBP custody to participate in a CFI in their destination city. If the family receives a positive CFI determination, they are unenrolled from FERM and they may proceed with applying for asylum, or other relief, before an IJ. If the CFI determination is negative, families may request a Negative Credible Fear Review (NCFR) of the AO’s decision by an IJ. If the decision is upheld, DHS will deport the family; if the decision is vacated, the family may proceed with a full asylum merits adjudication, or seek other relief from removal, before the immigration court.

This process, which allows families to reside with family and friends in their communities pending their CFI is a welcome policy shift, despite the use of surveillance mechanisms which continue to subject asylum seekers to overreaching and damaging carceral treatment, because it provides families with greater opportunity to access both family/community supports and counsel throughout their CFI proceedings.

With this framing in mind, in May 2023, Americans for Immigrant Justice (AI Justice), with the expert technical assistance of the Fordham Law School’s Feerick Center for Social Justice, established Familias Seguras (Safe Families)—a pro bono legal services project aimed at providing legal orientation, consultation and representation to families enrolled in FERM. Over an 11-week period, AI Justice has been contacted by 164 families enrolled in FERM: providing 27 families with pre-CFI Know Your Rights (KYR) information only; preparing 56 families for their CFIs; accompanying 11 families during their CFIs; and representing 13 families before the IJ following a negative finding of credible fear. Staff has also conducted six in-depth advocacy questionnaires with families to learn more about how they experienced the FERM process.

This report synthesizes AI Justice’s experience providing services to FERM families. It aims to provide insight into the early implementation of this program, highlight ongoing challenges faced by families and legal service providers, and suggest improvements to the process. Case examples and quotes in this report come directly from AI Justice client experiences; pseudonyms have been used to protect their identities and are denoted with an asterisk following the name. Throughout the report, the sample number in various data sets shifts, due to gaps in the information the AI Justice team gathered from FERM families. For example, although AI Justice has been contacted by 164 families, the team only was able to take note of the nationality information for 141 families. This is a result of the team’s primary focus on providing immediate legal orientation and consultation to families and reflective of the constraints non-profit legal service providers face in expedited processes.

Key Findings

AI Justice believes all individuals who seek protection and safety in the United States deserve full and fair access to the U.S. asylum system, and our work with FERM families does not condone the government’s use of expedited removal or carceral alternatives to detention. Rather, in recognizing the positive equities of initial release of families into the community instead of detention, Familias Seguras aims to provide comprehensive legal services to FERM families to protect their individual rights, stress-test this new policy, and push for rights-based and family-centered improvements to the process.

Our experiences providing orientation and consultation to families in FERM has led to the following key findings:

- Families need more time to address their immediate needs (including but not limited to housing, healthcare, and childcare) before they participate in a CFI.

- Early access to legal service providers ensures families enrolled in FERM understand the process. Early access is currently highly dependent on which FERM city a family is enrolled in.

- Even with early access to legal service providers, FERM’s current timelines make meaningful access to counsel at the CFI and NCFR stages difficult.

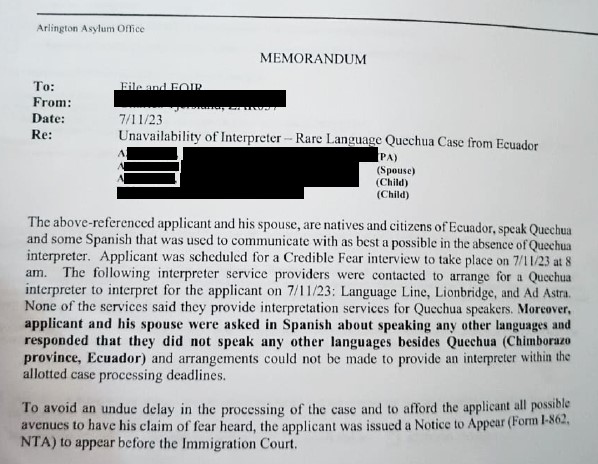

- Rare language speakers experience language barriers throughout the credible fear process that impact their ability to fully understand and participate in their CFI.

- Asylum offices require additional resources, training, and authority to effectively respond to the unique needs of released families in CFI proceedings.

- Families who live further afield from USCIS offices and Immigration Court locations face significant challenges travelling to FERM-related appointments.

- The separation of 18-, 19- and 20-year-old children of FERM lead applicants creates inefficiency in credible fear proceedings by increasing the possibility of conflicting credible fear determinations.

- FERM families are categorically subjected to various forms of electronic monitoring and a home curfew without individualized assessment of whether such monitoring is necessary to ensure compliance with FERM requirements.

- The asylum ban is applied to individuals in FERM without meaningful assessment of exceptional circumstances, including age.

- Legal service providers need more notice, funding, and support to provide meaningful access to legal services for families enrolled in FERM.

Recommendations

- Slow the expansion of FERM until additional training, resources, and infrastructure have been developed and implemented.

- Develop and provide additional training and guidance to AOs specific to released family units and make this guidance publicly available. This guidance should include, but is not limited to:

- Rescheduling requests;

- The right to consultation;

- The exceptionally compelling circumstances standard for rebutting the presumption of asylum ineligibility under the asylum ban (with a focus on assessments for minors);

- Safeguarding the right to confidentiality for parents, legal guardians, and children; and

- Procedures for ensuring parents, legal guardians, and children have access to necessary breaks during the CFI.

- Expand the timeline of the FERM program and ensure the basic needs of enrolled families are prioritized over strict compliance with any newly developed timelines, by:

- Increasing the time between when a family is released from custody and when their CFI occurs;

- Increasing the time between when a family is served a negative credible fear determination and when their NCFR is docketed before an IJ;

- Counting business days, not calendar days, in creating timelines; and

- Tracking overall fairness, not compliance with set timelines, in assessments of the FERM process.

- Increase early access to information and legal service providers by:

- Orienting families to the FERM process and credible fear proceedings prior to release from immigration custody and during initial appointments with ICE and ISAP;

- Providing families with a hard copy of a FERM-specific legal service provider list upon release from immigration custody, and re-distributing this list through the process, including during appointments with ICE, ISAP, the AO, and at a NCFR hearing;

- Increasing access to legal orientation and consultation for families in FERM by funding legal service providers; and

- Developing and disseminating city-specific advanced written notice to enrollees in relation to the logistics of the CFI, including how long the interview may last; where family members and children may wait during the interview; the availability of a playroom, television, or other distractors for children; access to food or drinks, etc.

- Publish a list with dedicated FERM points of contact and email addresses (either city- or region-specific) with capacity to quickly respond to time-sensitive issues, including CFI reschedule requests, accompaniment requests, rare-language notifications, instances of family separation, etc.

- Stop enrolling rare-language speakers in the FERM process and ensure rare-language speakers erroneously enrolled are swiftly unenrolled. Provide additional training to AOs and CBP agents regarding best practices for identifying if a person is a rare-language speaker and confirm that credible fear applicants have the right to interview in their preferred language.

- Reduce the geographic distance criteria used for FERM enrollments to 30 miles from the designated interview and immigration judge review locations.

- Eliminate the categorical use of electronic surveillance and home curfews for FERM families.

- Release 18-, 19-, and 20-year-old children of FERM lead applicants with their parent/s and sibling/s.

- Schedule families who receive negative credible fear determinations for NCFR hearings no sooner than five calendar days after the negative decision is served.

An Overview of the FERM Process

DHS officials processing a family who has recently arrived at the southern border have the authority to (1) parole a family into the United States without further processes, (2) refer the family to immigration court for removal proceedings under INA 240, or (3) issue them an expedited order of removal under INA 235. In the past, families placed in expedited removal were detained in an ICE family detention center pending their CFI. Under FERM, certain family units placed in expedited removal are released under electronic surveillance to participate in their credible fear proceedings from specific cities in the United States.

A family unit, or FAMU, is considered by DHS as a group of two or more individuals consisting of a “minor or minors accompanied by his/her/their adult parent(s) or legal guardian(s).” This is distinct from what DHS considers a “family group,” which consists of children aged 18 or older and additional family members (aunts and uncles, cousins, grandparents, etc.). DHS has confirmed that they consider only family units to be eligible for the FERM process.1

The DHS’s use of the FAMU definition for families enrolled in FERM can lead to family separation and inconsistent adjudication of similar asylum claims. AI Justice represented one mother whose 19-year-old-son was separated from her and her other children when they were enrolled in FERM and released to family in New Jersey, while her adult son was detained in an ICE facility in Eloy, Arizona pending a separate CFI proceeding. Children under the age of 21 are considered dependents for purposes of asylum claims, therefore, the separation of families with some children aged 18-20 for purposes of enrolling only “FAMUs” in FERM is inconsistent with U.S. asylum law. AI Justice contacted ICE Headquarters about this case, requesting the son be released and enrolled in FERM with his family; this did not occur. In this instance, the son passed his CFI and was released from ICE detention, where he has been able to reunite with his mother and siblings, who received positive credible fear determinations through the FERM process.

According to ICE, families are selected for enrollment in FERM based on multiple factors, including their nationality (specifically, if they are from a country with regularly scheduled removal flights), their intended destination city, whether the head of household is eligible for placement in ICE’s surveillance-based Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program (e.g., whether they have a medical condition that would prohibit the use of an ankle monitor, such as being pregnant or nursing), and encounter trends (i.e., how many families from a certain country are being apprehended at the border).2

Prior to release from CBP custody, the family is enrolled in ICE’s problematic surveillance-based ATD program, which includes placement of a GPS-enabled ankle monitor on the head of household, a curfew which requires them to be in their home between 11 PM and 5 AM, and electronic monitoring via a SmartLink device. For families with both parents enrolled in FERM, only one person is identified as the head of household. It is unclear how CBP identifies who is the head of household in a dual parent household enrolled in FERM.

Families are released with an appointment to present at their local BI, Inc. office to further enroll the family in the FERM process upon arrival in their destination city. BI, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of the GEO Group, a private prison company, is the private corporation contracted by ICE to facilitate DHS’s Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP). During this initial ISAP appointment, families are provided with additional information regarding ICE’s surveillance-based ATD program and FERM by BI Inc. employees, not government officials. BI, Inc. is also contracted to provide families with additional information and referrals to social services, such as housing, access to healthcare, etc.

1 Information provided at a July 2023 ICE stakeholder engagement meeting regarding the expansion of FERM.

2 Information provided by DHS at various stakeholder engagement sessions regarding the implementation and expansion of FERM

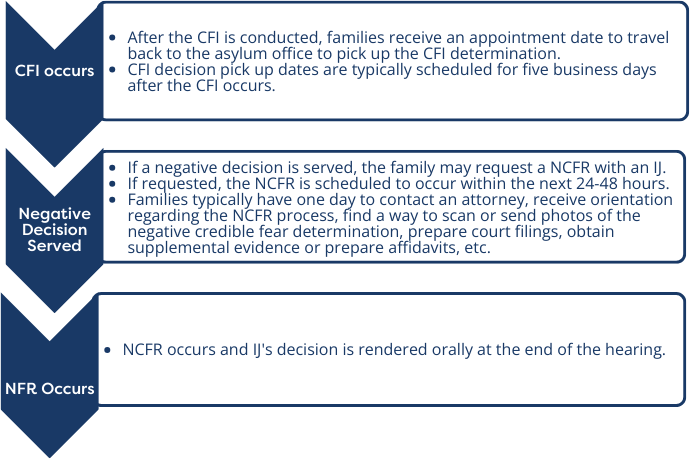

Timeline of the FERM Process

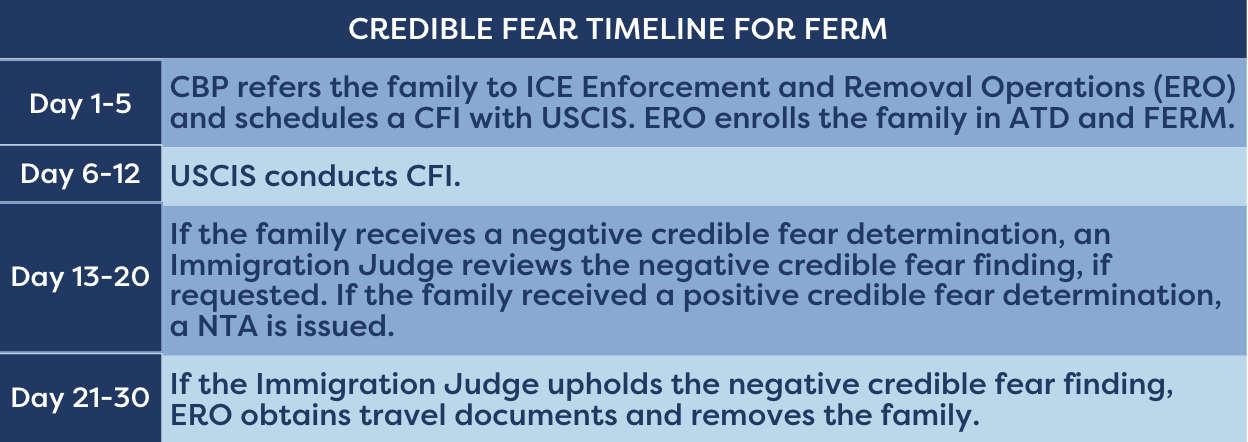

Under the FERM process, a family’s credible fear proceeding (which includes the CFI and NCFR) is scheduled to conclude within thirty days of the family’s release from CBP custody.

During the CFI, families present their fear of return to their home country to an AO who decides whether they have shown a “significant possibility” of prevailing on a claim for asylum, withholding of removal, or relief under the Convention Against Torture. Currently, credible fear applicants who enter without inspection and do not meet a limited number of exceptions are subject to the asylum ban and being held to a heightened “reasonable possibility” standard. Although the asylum ban was found unlawful by a Federal Judge on July 25, 2023, that ruling is currently stayed pending appeal and the rule is still in effect at the time of this report’s publication.

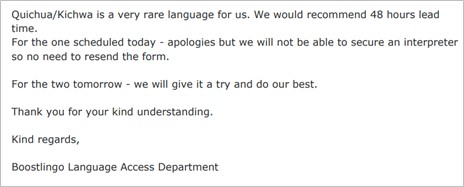

Importantly, an AO must terminate credible fear proceedings and issue a language access or “rare-language” NTA in all cases where an individual’s preferred language is not serviced by translation services available to the asylum office and the individual does not agree to proceed in another language. AI Justice has seen a high number of rare-language speakers enrolled in FERM who, after stating that their best and preferred language was a rare-language, were guided by AOs to proceed in the Spanish language. Many of these families were subsequently issued negative CFI and NCFR determinations. More information about this practice is provided in the ‘AI Justice’s Observations’ section.

If, after a CFI, the AO issues a family a positive credible fear determination, they are issued Notices to Appear (NTA) before the Immigration Court to proceed with their application for asylum and other protections in full removal proceedings under INA Section 240.

If, after a CFI the AO issues a family a negative credible fear determination, the family has the right to request that an IJ review the negative decision in a NCFR hearing. If the negative determination is upheld by the IJ, the family’s order of expedited removal becomes final, and deportation occurs swiftly. The experience of people placed in FERM and ICE’s own program description suggests that families that receive a negative IJ determination will ordinarily receive a letter from ICE providing a date and time when they will be required to check in for removal. Upon reporting to an ICE location, “ICE will briefly assume custody and escort the FAMU (family unit) to their pre-scheduled removal flights.” 3

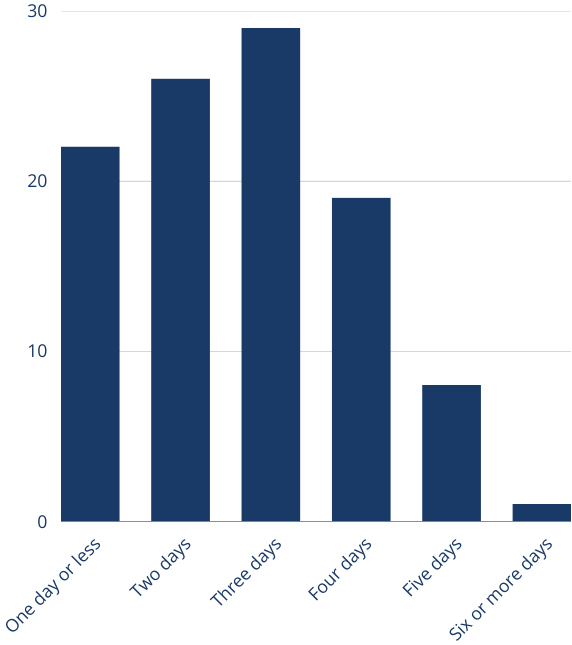

According to presentations provided by ICE to legal service providers regarding the creation and expansion of FERM, the established credible fear timeline for FERM is as follows:

During AI Justice’s work with FERM families, staff have identified additional trends presumed to be government benchmarks in the FERM timeline. First, FERM families are generally scheduled for their first ISAP check-in for further enrollment in the FERM process within three days of their release from CBP custody. Following the CFI, with few exceptions, families are required to return to the asylum office approximately five business days after their interview to be served with their credible fear determination. Additionally, when the asylum office issues a negative credible fear determination, the NCFR hearing is generally scheduled to occur one or two business days after service of the negative fear determination.

AI Justice has also observed that the timing between the initial ISAP check-in and the CFI varies in relation to the FERM destination city. For example, CFIs in Baltimore generally occur just 1-2 days following the initial ISAP check-in, whereas in San Francisco, CFIs appear to be scheduled 3-4 business days after the ISAP check-in.

FERM Locations

Since its initial launch in four destination cities, the FERM process has rapidly expanded to thirty-three cities across the United States as of September 1, 2023. The following is a table of the cities and dates enrollments began.

| May 10, 2023 | Chicago, IL; Baltimore, MD; Washington, D.C.; and Newark, NJ |

| June 23, 2023 | Denver, CO and Minneapolis, MN |

| July 28, 2023 | New Orleans, LA and Houston, TX |

| August 4, 2023 | Boston, MA; Providence, RI; San Jose, CA; San Diego, CA; and San Francisco, CA |

| August 11, 2023 | Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; Philadelphia, PA; San Bernardino, CA; and Portland, OR |

| August 18, 2023 | Las Vegas, NV; Marlton, NJ; Sacramento, CA; Los Angeles, CA; and San Antonio, TX |

| August 25, 2023 | Manassas, VA; Charlotte, NC; Phoenix, AZ; Silver Spring, MD; and King of Prussia, PA |

| September 1, 2023 | Kansas City, MO; Indianapolis, IN; Santa Ana, CA; New Brunswick, NJ; and Atlanta, GA |

Continued and rapid expansion of the FERM process is expected to continue until 40 cities have been brought into the program.4

Data on FERM Enrollments

According to information provided by DHS officials to legal service providers at various stakeholder engagements, as of August 23, 2023, approximately 1,000 families have been subject to the FERM process, with approximately 500 families currently enrolled. Most recently, DHS has stated that they are enrolling up to 125 families each in the initial FERM locations of Baltimore; Chicago; Denver; Houston; New Orleans; Newark; St. Paul; and Washington, D.C., while capping enrollments at 50 families per each additional FERM location. However, this metric appears to be constantly changing.5

3 Information provided by DHS at a May 2023 stakeholder engagement meeting regarding the implementation and expansion of FERM.

4 Information provided by DHS at an August 2023 stakeholder engagement meeting regarding the implementation and expansion of FERM.

5 Information provided by DHS at an August 2023 stakeholder engagement meeting regarding the implementation and expansion of FERM.

AI Justice’s Observations

In early June 2023, AI Justice, with the support and expertise of the Feerick Center for Social Justice, launched Familias Seguras, a project aimed at providing legal orientation and pro bono representation to families subject to FERM. Over an eleven-week period, AI Justice staff have spoken with approximately 164 families enrolled in the FERM process, all of whom reached out affirmatively to the Familias Seguras hotline.

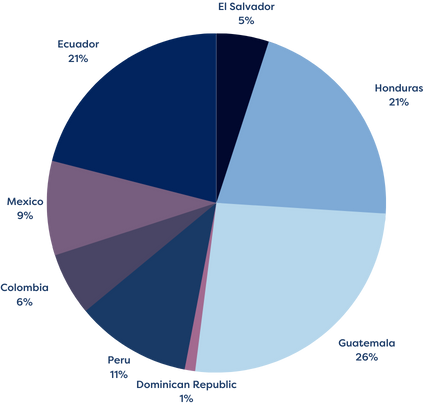

Out of the 141 families for which AI Justice has data regarding nationality, staff have spoken with family units from Guatemala (36); Honduras (30); Ecuador (29); Peru (15); Mexico (13); Colombia (9); El Salvador (7) and the Dominican Republic (2). While this data is not representative of total enrollments in FERM, it helps to demonstrate some of the countries of origin of families enrolled in FERM.

Country of Origin

Additional demographics of note from AI Justice’s experience include the following:

- Out of 162 families, 135 families were single parent head of households and 27 families consisted of double heads of household (i.e., two parents).

- Out of 122 families, 85 families were single-child units and 37 families consisted of two or more children.

- Based on information from a total of forty children, the average age of a child enrolled in FERM was approximately 7.5 years old. The oldest child was 17 years old, and the youngest child was 8 months old.

1. Early access to legal services increases the likelihood families placed in FERM understand the nature and purpose of their CFI and other obligations they have during their immigration process.

Legal service providers can play a critical role in helping families understand the FERM process, as attorneys are uniquely placed to explain the FERM process to families and help them understand the importance of preparation and full participation.

Upon initial contact with AI Justice, many families are confused about the FERM process. They do not fully understand the distinction between their ISAP check-ins and the upcoming CFI with an AO or the purpose, requirements, or potential implications of the CFI. Although some families in the FERM process have family members or friends who have personal experiences with the immigration system, the FERM process is new, thereby creating a level of confusion based upon informal information networks.

DHS can eliminate confusion about the FERM process by providing families with information about the process as early as possible and multiple times, in various ways. This education is critical given the complexities and speed of the FERM process and the misinformation families must navigate through caused by word-of-mouth advisals from family members and friends. Families should be provided oral advisals regarding the nature and purpose of the CFI process before their release from immigration custody. This information should be provided to families again during the initial ISAP appointment and again, through systemized access to legal orientation provided by experienced and trusted legal services providers.

The rapid expansion of FERM before matching infrastructure for legal orientation was established has impacted the fairness of the process, as families have been forced to participate in CFIs without fully understanding the purpose and potential outcomes of their interview. Many asylum seekers are fearful of sharing the details of their past persecution and fear of returning to their home country, a natural reaction for many individuals with subjective fear and trauma. Other asylum seekers are reticent to talk about their case out of fear that sharing the details of their story with a U.S. government official will lead to government officials in their home country discovering such information, a common fear of victims of state-sponsored violence.

AI Justice has repeatedly observed the positive impact of legal orientation on an individual’s ability to testify to their past harm and fear of future harm during a CFI.

Talking with Ms. Sofana before my interview helped me a lot. She explained to me what type of questions the asylum officer would ask me and why they were asking these personal questions. At first, I did not want to answer the questions she asked me, but she helped me to feel more confident to talk about my story. I think things would have been very different without her.

— Client enrolled in FERM Newark who received a positive credible fear determination after speaking with AI Justice staff member, Sofana Castellon.

Only after a thorough legal orientation and clarification that CFI transcripts are not shared with home governments do many individuals have the courage to disclose their past experiences of harm and torture to an AO. While access to meaningful and thorough legal orientation empowers an asylum seeker to participate in their CFI more meaningfully, it must not be viewed as an alternative to individual legal consultations and representation.

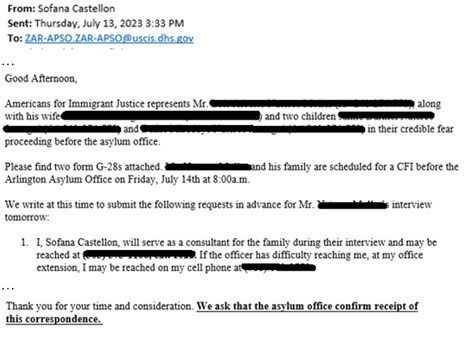

2. Early provision of relevant legal service provider information is critical in securing access to counsel given the tight timeline of the FERM process.

While DHS has not released specific statistics regarding representation rates in FERM, based on AI Justice’s data and available information, representation rates appear to be very low for FERM families. On June 2, 2023, AI Justice provided a flyer to DHS for distribution to families in FERM (Appendix A). DHS informed AI Justice that Familias Seguras was the only legal service project offering representation to families in FERM at that time. AI Justice has spoken with 164 families out of the approximately 1,000 families that have been subject to FERM as of August 23, 2023; meaning Familias Seguras has only been in contact with approximately 16% of all FERM families. While AI Justice is aware of some instances of representation from the private bar and other non-profit organizations, staff believe these numbers to be quite limited during the 11-week period under discussion.

Based on call volume and geographic location, AI Justice does not believe that the Familias Seguras flyer was distributed consistently by government officials or contractors. For example, the majority of initial outreach to the Familias Seguras hotline came from families enrolled in FERM in Baltimore, MD who were being given the flyer by their BI case manager. Calls from the Newark, NJ area started to increase after AI Justice staff met with the Mid-Atlantic Regional Manager of BI to discuss Familias Seguras’s legal services. In mid-July, the team began receiving calls from families in NCFR proceedings in Washington, D.C., who referred to the project by an IJ. And shortly after San Francisco, CA came online as a FERM city, Familias Seguras began receiving a multitude of calls from families enrolled in that city facilitated by families, BI case managers, and AOs. Additionally, some border welcoming groups have begun to share AI Justice’s hotline information with identified FERM families upon their release from CBP custody.

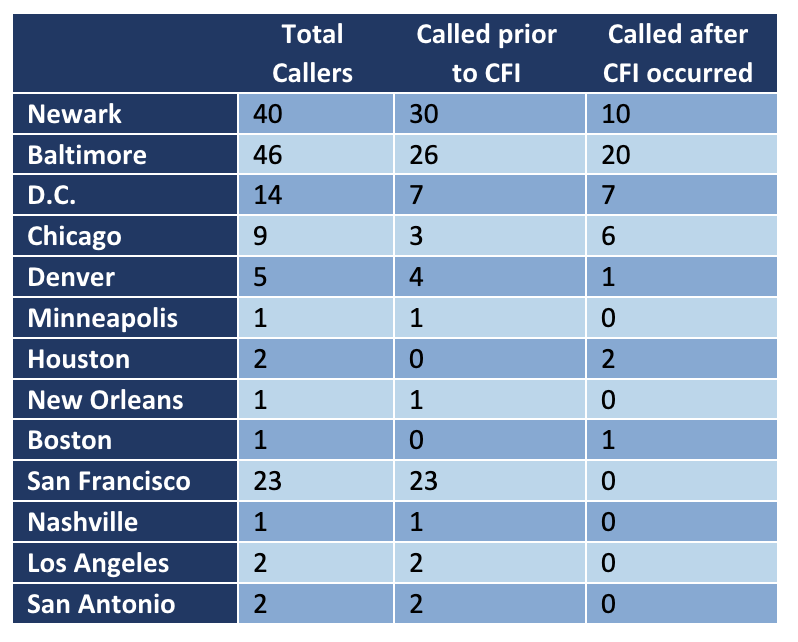

A review of the number of families who have called from different FERM cities shows the piecemeal manner in which AI Justice believes the Familias Seguras information is being distributed.

Calls Received by AI Justice Based on FERM City Enrollment

The above chart indicates the number of families who have called from different FERM cities based on the available data from 147 families. The cities are presented in the order in which they were added to the FERM program. As demonstrated, there are numerous cities in which Familias Seguras has received very few calls from families, and a handful of cities with active enrollments during the relevant 11-week period from which AI Justice received no calls—specifically, Providence, RI; San Diego, CA; Seattle, WA; Philadelphia, PA; San Bernardino, CA; Porland, OR; Las Vegas, NV; Marlton, NJ; and Sacramento, CA. Similarly, although Washington, D.C. and Chicago, IL are two of the initial FERM cities, most calls from families in Chicago and Washington D.C. to the Familias Seguras hotline occurred after the family obtained a negative credible fear determination. However, without official data regarding the number of enrollments in these cities, it is difficult to conclude whether families in these destination cities were not provided information regarding FERM-specific legal service providers or FERM enrollments were simply low or non-existent during this time.

In an early survey of AI Justice’s first six FERM families, only two families reported receiving a list of legal service providers upon being enrolled in the FERM process while in CBP custody. The remaining four families stated that the first time they received a list of potential legal service providers was at their ISAP appointment, which usually occurs just days prior to the CFI. Through a review of client records, many families enrolled in the FERM process during the early weeks of the program received a full list of legal service providers before the specific immigration court of their destination city; however, these organizations do not specifically provide services to FERM families. For example, Baltimore-placed FERM families received the seven-page list of Maryland-based immigration legal services provided in other immigration contexts—not a FERM specific list or the Familias Seguras flyer. It is also important to note that DHS has rapidly expanded the FERM process without sufficient advanced coordination with local service providers to ensure that they have the resources and capacity to contact families before their interviews and hearings.

Additionally, when a family contacts AI Justice depends on when the family received Familias Seguras contact information. In some cities, such as San Francisco, the Familias Seguras hotline regularly receives calls from families prior to their CFI; in other cities, like Chicago, the Familias Seguras hotline primarily receives calls from families after a negative CFI determination has already been issued by the AO. AI Justice has also seen changes in these trends—for example, the first group of FERM families in Washington, D.C. called AI Justice immediately prior to their NCFR; however, based on more recent calls, families from D.C. appear to be receiving the Familias Seguras hotline information prior to their CFI.

In mid-August, the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR) published and began sharing with new enrollees a FERM-specific legal service provider list (Appendix B). At the time of publication of this report, AI Justice has yet to see how this new list impacts the number of FERM families who contact Familias Seguras upon enrollment in the process and prior to their CFI.

3. Families require more time to recover from their arduous journeys and adjust to their new settings before consulting with legal service providers prior to their CFI.

Arriving at their final destination and reuniting with family or friends is usually the last step in a harrowing journey for many families seeking asylum. However, under FERM, it is just the beginning. Individual journeys to the United States can be extremely dangerous and difficult—especially for families traveling with children—and conditions in CBP custody are notoriously bad. Families need time to recover from the conditions of their escape and journey and to acclimatize to a new home environment before shifting focus to their immigration proceedings.

The truncated timeline of the FERM process, which envisions CFIs occurring between days 6-12 of release from CBP custody, does not allow families sufficient time to prepare for their CFI. On average, it took families surveyed by AI Justice two days to travel from the border to their destination city. Families reported long travel days from border shelters to their destination cities. One family was required to take a 4-hour bus ride to the airport and then spend the night sleeping on the floor before their flight to Newark the next day. Upon arrival in their destination cities, most families report being happy to have arrived, but also very tired, with one family stating, “We had a hard time . . . in CBP custody. We were awake almost 24 hours a day. We were uncomfortable all of the time.”

Upon arriving at their final destination, families must navigate multiple additional challenges including accessing basic necessities like infant formula, food, clothing, or medical care, enrolling in school, and arranging for access to a telephone and internet.

AI Justice has worked with many clients struggling to address health issues—ranging from children with stomach issues or fevers to families with suspected COVID or even more serious issues—while complying with the numerous requirements of the FERM process.

I felt unwell upon my arrival to the United States, but it wasn’t until after my credible fear interview that I first went to the doctor. I needed to rest but was not able to because I was worried about my hearing before the judge. After the hearing was over, I was so sick that I had to be taken to the hospital where I had to stay for eight days. I had a serious health issue called sepsis caused by failing to treat an infection.

— Client placed in FERM Arlington

Upon arriving at their sponsor’s home, families must also settle into their new living situation. This often means reconnecting with family members who the parent(s) have not seen in many years—and who their child may never have met before—or living with relative strangers, in-laws, or other new acquaintances. These transitions can be particularly difficult for children to navigate, especially given the trauma and coping mechanisms many have adopted during their difficult journey to the United States. Parents in FERM must regularly balance caring for their children while simultaneously speaking to a myriad of government officials and contractors, all while finding time to speak with a legal representative.

Our staff regularly works with mothers who are simultaneously caring for their children while receiving a Know Your Rights presentation or individual consultation. Many times, our clients’ children refuse to leave their parent’s side, or the client has no other childcare option. Our staff are trained to ensure the client feels comfortable proceeding with discussing their legal claim with their children present and we offer to reschedule whenever possible. However, given the tight timelines in which we are working, often times we cannot reschedule a legal consultation for a later date. It’s not uncommon for us to take short breaks in our conversations so a parent can calm a crying child or have to repeat ourselves numerous times because a client cannot concentrate or hear over their child’s cries or laughter.

— Jovita Salas, Managing Attorney of AI Justice’s Asylum Project

AI Justice has also worked with many clients who do not have their own phone and must instead rely on borrowing a family member’s or friend’s telephone to speak with legal counsel. Our legal staff typically spend between 3-6 hours on the phone consulting with each family, sometimes over the course of multiple calls. Given the other needs that families, especially single parents, are juggling, it is not always possible to complete a legal consultation in one day. AI Justice staff have struggled to get back in contact with a handful of individuals who call the Familias Seguras hotline using a borrowed phone and to schedule a time to speak with potential clients who must balance scheduling a consultation based on ability to borrow a telephone.

Ericka* did not have her own phone upon placement in FERM. Due to the work hours of her aunt and cousin, she was unable to borrow a cellphone during normal business hours until the day of her CFI, when her cousin took off work to take her to the interview. Ericka’s CFI was scheduled for 8 AM, so she wasn’t able to call the FERM hotline until after her CFI had occurred.

The only time I was able to call the lawyers was after my interview, because my family members were usually at work during the day. When I first arrived, I had nothing of my own, it was very difficult for me. I wanted to call the legal help telephone number sooner, but I did not have an opportunity. I was able to get a cell phone of my own four days after my interview.

— Client placed in FERM Arlington

Despite these various interpersonal and familial challenges, the FERM process requires families to immediately focus on their immigration proceedings at the expense of addressing their most basic, immediate needs. Initial ISAP appointments typically occur between 1-3 days after a family arrives at their final destination, with CFIs being scheduled in some cases as soon as the day after the initial ISAP check-in.

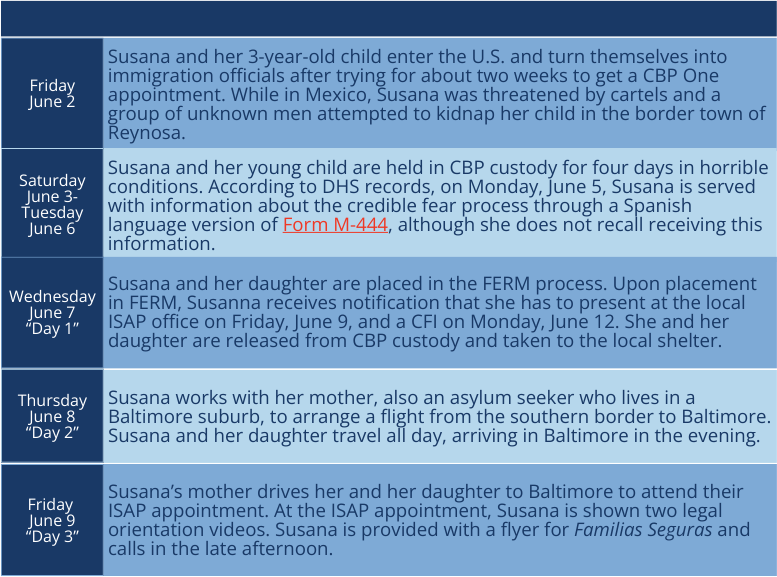

Below is a timeline of Susana’s* case, which highlights the numerous challenges and stress this vulnerable client and her family underwent because of the extremely tight timeline of the FERM process.

4. The current FERM timeline is too short for families to exercise their right to consult prior to their CFI.

In addition to families needing more time to acclimate and address urgent needs prior to consulting with legal counsel, legal service providers also need more time to thoroughly provide meaningful counsel to families in FERM.

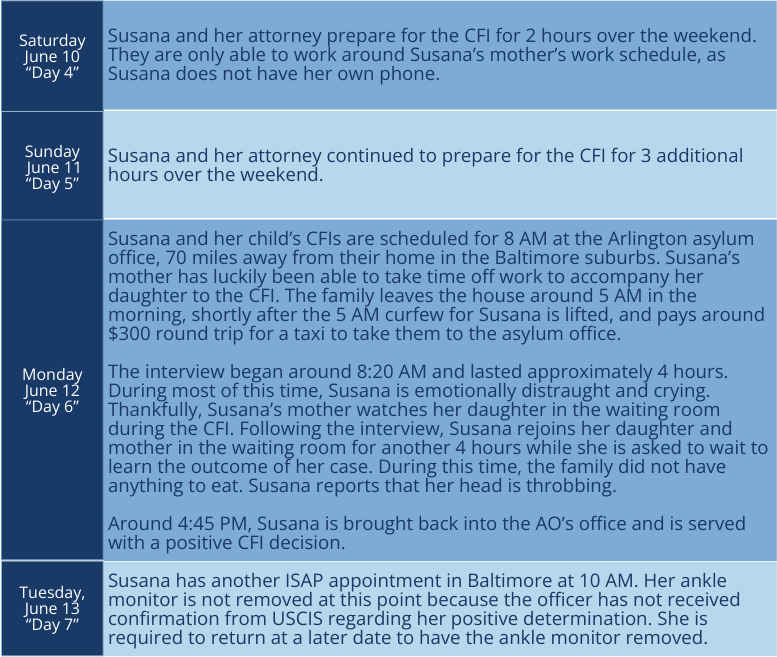

On average, out of fifty-one families, CFIs occurred ten days after a family’s initial release from custody, with the soonest interview occurring six days following the family’s release from custody. At the same time, it took an average of 9.5 days for families to reach out to AI Justice following their release from CBP custody.

While approximately 72% of families who reach out to AI Justice were able to do so prior to their CFI, with the average family reaching out approximately three business days before their CFI, this still leaves very little time for AI Justice staff to reach back out to a family, conduct an intake interview, provide a legal orientation and an individualized case consultation. While staff have been able to prepare the majority of these families for their interviews in an expedited and truncated manner, more time is needed to provide trauma-informed and thorough preparation. The AI Justice team has spent substantial time after business hours and on weekends providing immediate response legal services to FERM families—an unsustainable pace for non-profit legal services.

Number of Business Days Before CFI When Families Called AI Justice

Preparing a family for their CFI is time intensive because each family member may have claims separate and apart from those of other family members. Each family member needs an opportunity to consult with counsel individually and privately.

The asylum ban also applies to families enrolled in FERM. Under the asylum ban, the presumption of asylum ineligibility can be rebutted if an individual can demonstrate “exceptionally compelling circumstances,” in relation to any member of the family that they travelled with. These circumstances include but are not limited to (1) acute medical emergency; (2) imminent and extreme threat to life or safety; and/or (3) being the victim of severe trafficking in persons. As such, it is critical that all family members be individually screened for an exception—a time consuming endeavor.

Additionally, minor children enrolled in FERM are also subject to the asylum ban, without further consideration as to the child’s age as an exceptionally compelling circumstance. Children are treated differently throughout the INA in consideration of their age. For example, the deadline for filing a motion to reopen is tolled for minors, the one-year deadline to apply for asylum is waived for minors, and minors cannot accrue unlawful presence. The asylum ban seeks to strip asylum eligibility from individuals who enter without inspection instead of entering through a small number of limited pathways. The exceptionally compelling circumstances speak to reasons why an individual might have needed to enter the United States under exigent circumstances and thus have not been able to seek entry through a pre-scheduled appointment. Minors traveling with family members lack the ability to decide for themselves how and by which manner they seek to enter the United States. They are innocent in the decision-making of their parents and should not be punished with being categorically stripped of their right to protection. AI Justice has made these arguments to the asylum office but has not prevailed.

Furthermore, AI Justice has noticed inconsistencies in the application of the asylum ban to its FERM clients. AI Justice is aware of two cases in which an exceptionally compelling circumstance was found to rebut the presumption that the asylum ban applied and many cases in which an exceptionally compelling circumstance arguably should have been found.

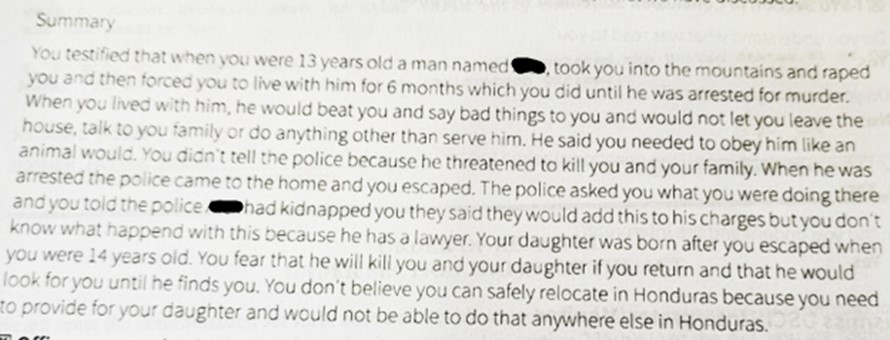

In one case in which the presumption was rebutted for being the victim of a severe form of human trafficking, the individual was coerced into forced labor and sex acts, beginning at age 14, for a period of four years by her stepfather, who beat her and threatened to beat her if she did not comply. The AO found the client to be a victim of a severe form of human trafficking and thus that the asylum ban did not apply. However, in a similar case, a client was raped, abducted, and held captive for six months at the age of 13, during which time she was forced to perform manual labor and sex acts under threat of death. In this instance, the AO did not find the individual to have been a victim of a severe form of trafficking, and the asylum ban applied.

In this case, despite the application of the asylum ban, the individual passed their CFI under the higher reasonable possibility standard applied by the AO. In the summary below of the individual’s CFI, the AO clearly lays out the trafficking situation the individual was subjected to.

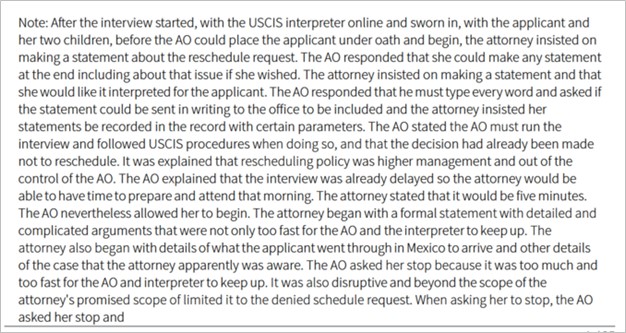

5. Requests to reschedule CFIs are inconsistently considered, not considered, or unjustifiably denied for families in FERM.

In AI Justice’s experience, the ability to reschedule a CFI varies based on the individual asylum office. AI Justice has had limited success rescheduling CFIs to facilitate access to legal services in most jurisdictions. Credible fear applicants who request to reschedule their interviews to allow for more time to consult with an attorney regularly have those requests denied. However, in some jurisdictions like San Francisco, the asylum office reschedules an applicant’s CFI upon request to facilitate access to consultation.

In one case, an AO in Arlington denied AI Justice’s request to reschedule without allowing counsel to detail the exceptional circumstances warranting the request be granted. In this case, the family contacted AI Justice shortly before the interview. The AI Justice attorney quickly submitted an electronic request to reschedule with a properly executed G-28. However, given the need to quickly submit this request, the written request did not detail the significant individualized reasons supporting it. When counsel was called at the outset of the CFI, she asked for the opportunity to detail the exceptional circumstances underlying the request to reschedule for consideration before the interview proceeded. The AO indicated the request was denied by a supervisor and would not further be considered, and advised the attorney that she could present the reasons for the rescheduling request at the conclusion of the interview. The attorney again advocated for the opportunity to detail the request for rescheduling before the CFI continued and to have the request documented in the record. After significant pushback, the AO agreed; however, the AO failed to consider counsel’s arguments. See below for an excerpt from this client’s CFI transcript.

In another case, AI Justice sent a time-sensitive written request to the Newark asylum office documenting observations in a client’s health reflective of a heart attack and/or panic attack. Counsel requested that the interview be rescheduled for the lead applicant to receive urgent medical care, or in the alternative, that the family be unenrolled from FERM. Counsel also indicated that she would accompany the family should the interview proceed and provided the asylum office her telephone number. The Newark asylum office did not respond to these urgent requests and the AO conducted the CFI without contacting counsel.

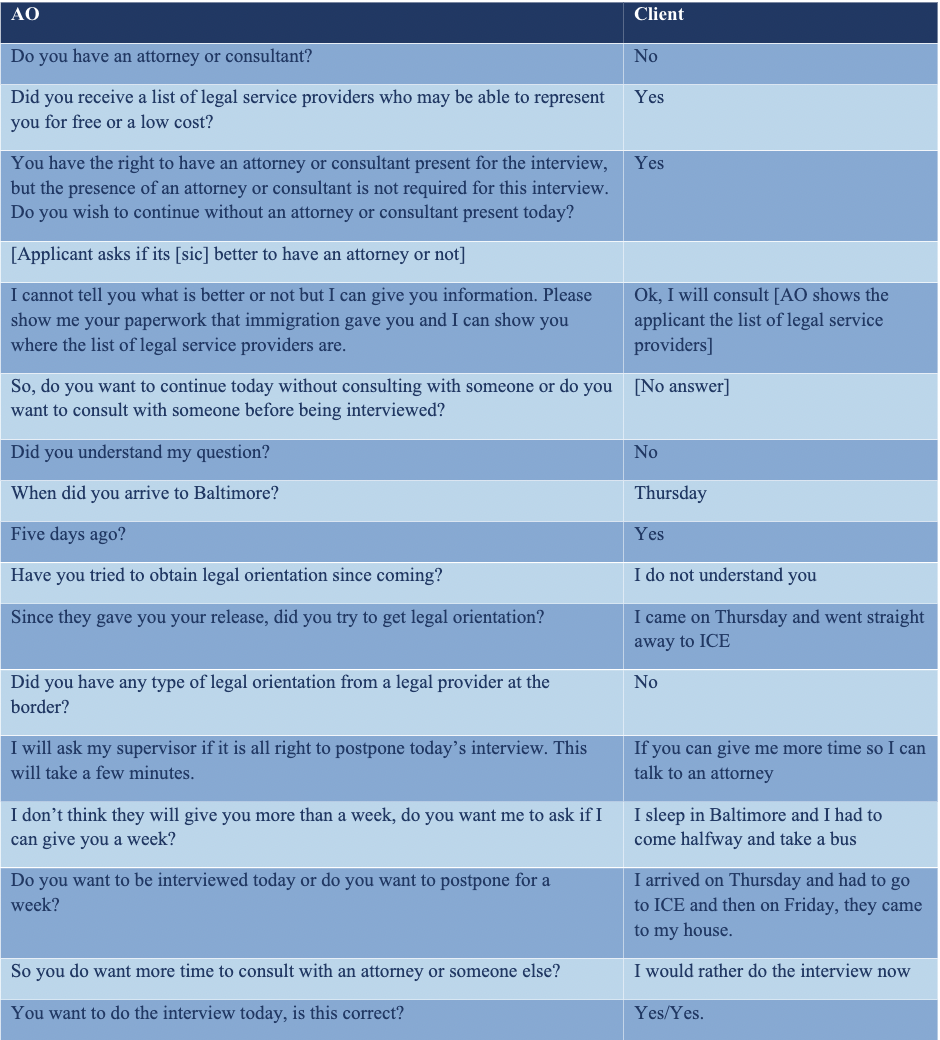

Additionally, staff have spoken with numerous families who were unable to access counsel prior to their CFI who stated their desire to do so at the outset of their CFI. In the overwhelming majority of these cases, the AO did not reschedule the interview to allow the family to exercise the right to consult. In one example, despite the individual explicitly asking for more time to speak with an attorney, the AO provided confusing guidance before proceeding with the interview. An excerpt of the conversation as described in the CFI transcript is below:

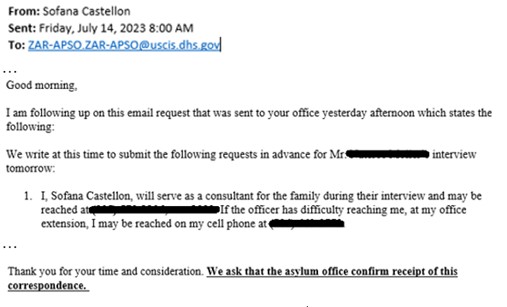

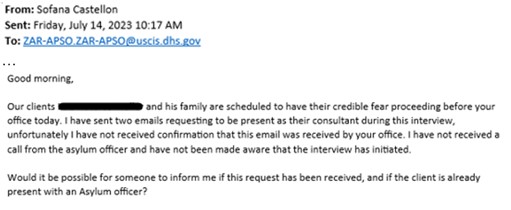

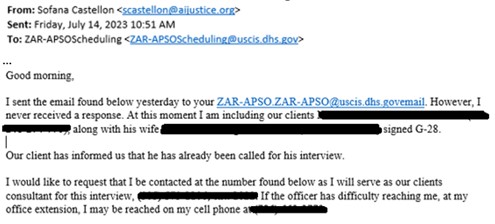

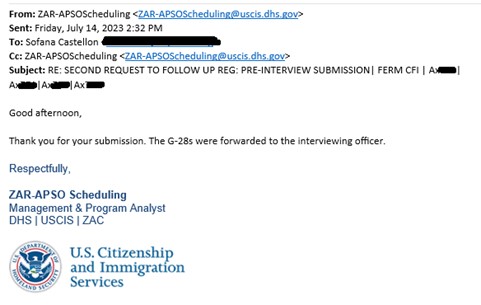

6. Some FERM families are being denied the right to consult with advocates during their CFI.

Individuals in CFI proceedings have the right to have “any person or persons” with whom they choose to consult be present at the interview. 8 C.F.R. 208.30(d)(4). AI Justice entered Form G-28 and advised the asylum office of accompaniment in more than a dozen cases and were able to participate in almost all of these cases. However, on a few occasions AI Justice was required to defend the right to be present during the interview as a consultant. In one instance, the AO would not allow a staff member to accompany a client because the consultant did not have their own G-28 on file. Despite explaining that the client had the right to consult with “any person” of their choosing, regardless of if that person was a lawyer or had a G-28 on file, the AO refused to let this AI Justice staff member accompany the family during the interview.

In another case in which AI Justice submitted a pre-interview G-28 and request to accompany, the asylum office did not confirm receipt or reply to the request until hours after the interview had occurred. The clients’ simultaneous requests that their counsel be contacted were ignored.

| First request |  |

| Second request |  |

| Third request |  |

| Fourth request |  |

| Response |  |

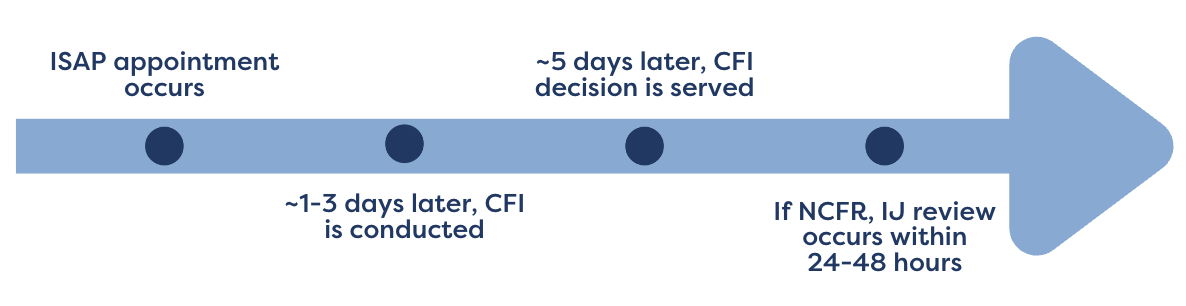

7. Families require more time to consult with counsel prior to their NCFR hearing.

In the case of a negative CFI determination, families have the right to request review of the decision by an IJ. Based upon AI Justice’s observations, NCFRs for families in FERM are typically scheduled less than two business days from the service of the negative decision. The overwhelming majority—almost 92%—of families that AI Justice has spoken to prior to their NCFR contacted AI Justice for the first time after receiving a negative credible fear determination. In many of these cases, the family presented with unique vulnerabilities, including at least six rare-language speaking families, one head of household with a severe speech impediment, and two heads of household with serious health issues that impeded their ability to testify. This implies that many families who need accommodations are unable to consult with legal counsel, adversely impacting their ability to meaningfully engage in their CFI, and leading to negative determinations.

Based on AI Justice’s experience, families are generally being asked at the time of service of the negative decision if they want an IJ to review the decision; they are not required to affirmatively and spontaneously request an NCFR. However, AI Justice is aware of at least one case in which a family was provided with misinformation regarding the NCFR process. In this case, the family initially declined to request IJ review of their negative CFI determination because the mother erroneously believed requesting IJ review would result in separation from her child. After speaking with the client, AI Justice requested that the family be re-served their negative decisions in order to request IJ review.

In order to provide meaningful consultation to a family who has been issued a negative credible fear determination, an attorney must first receive and review the family’s credible fear record. It is difficult for families to quickly scan and email their credible fear determination given the likelihood that families do not have access to the necessary technology in their home and their limited knowledge of community resources, such as a local business where they can access this technology, Given these challenges, AI Justice quickly requests CFI records from the AO and enters a G-28 for that purpose. Based upon AI Justice’s experience, the asylum office often times responds to these requests more than 24 hours after they are made. Given FERM’s fast timeline, even a 24-hour delay obstructs a family’s ability to consult before their NCFR hearing. In most cases, in order for AI Justice to review the negative CFI determination, families have had to send photos of each page of their documents to AI Justice staff one-by-one through text messaging. Only one potential client had access to a computer and scanner. Simply receiving the complete record of the negative determination to begin preparation for IJ review could take hours, as often times families are unable to send these photos right away.

Once an attorney files an E-28 on the EOIR Courts and Appeals System (ECAS), an electronic case management system, the attorney has access to the individual’s CFI transcript and any other documents on file with the court. However, given a lawyer’s need to assess the case prior to entering an appearance, this reality does not cure the asylum office’s delay providing counsel with a copy of the credible fear record.

The speed in which NCFRs are scheduled stands in juxtaposition to the length of time the asylum office is afforded to prepare and serve a CFI decision. In AI Justice’s experience, most families are served their CFI determination five business days (seven calendar days) after the conclusion of their CFI. In contrast, NCFR hearings are scheduled 1-2 business days after the day the CFI determination is served. While 8 CFR § 1003.42 requires IJ review occur “to the maximum extent practicable within 24 hours, but in no case later than 7 days” after a negative decision is issued, it is not practicable to conduct an NCFR within such a short timeline for non-detained families, especially given the unique circumstances families in FERM face, as described throughout this report.

NCFR Timeline

Given these realities and the timeline of the regulation, AI Justice recommends that NCFRs be scheduled no less than five calendar days after a negative credible fear determination is served. This change would promote judicial economy. In certain circumstances, IJs have rescheduled NCFRs upon learning that the family has not been able to access legal counsel. For example, at least four families contacted Familias Seguras after being given the legal services flyer by an IJ, who rescheduled their hearing to allow for attorney consultation. Additionally, AI Justice has been successful on numerous occasions in continuing an NCFR to allow for more attorney preparation given the tight timeline of the proceedings.

AI Justice has participated in 11 out of the 13 NCFR cases in which staff submitted an E-28. AI Justice was denied the ability to participate in two NCFRs before the same IJ in Newark despite having an E28 on file. In the first instance, counsel had less than 24-hours’ notice of the NCFR from the client and was unaware that the IJ did not allow Webex appearances. In the second instance before this IJ, counsel submitted a motion to appear telephonically, which was denied. The need for attorneys of record to file motions for telephonic appearance and determine additional filing preferences and procedures for specific IJs and immigration courts weigh further in support of scheduling NCFRs for released families no sooner than five calendar fays after service of their negative decision.

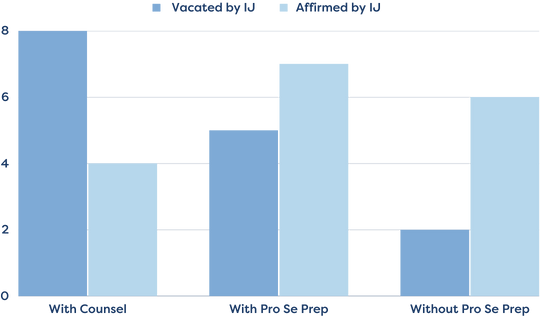

8. Adequate time to consult with counsel is critical.

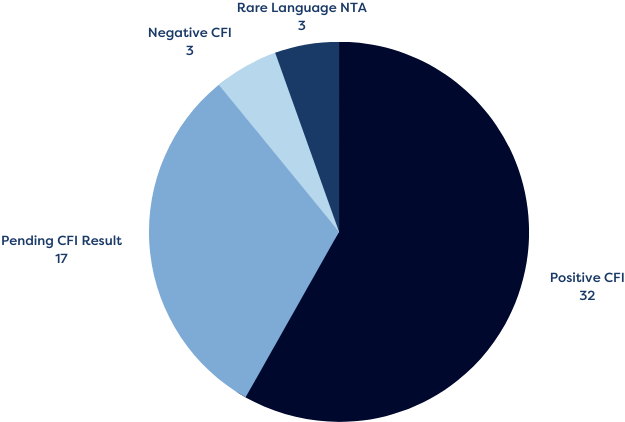

Based on AI Justice’s experience, out of a total of 136 families, families who received a legal consultation prior to their CFI had a 92% pass rate; whereas families who did not receive an individualized legal consultation passed at a rate of only 43%. Additionally, out of a total of 32 families, families with access to legal service providers prior to their NCFR, whether they received KYR information, pro se prep, or were represented by counsel, were 34% more likely to have their negative decision vacated by the IJ. These numbers show that legal consultation and representation increases an AO and IJ’s ability to fully understand a family’s claim of fear.

Outcomes for Families Provided Legal Counsel Prior to CFI

NCFR Outcomes

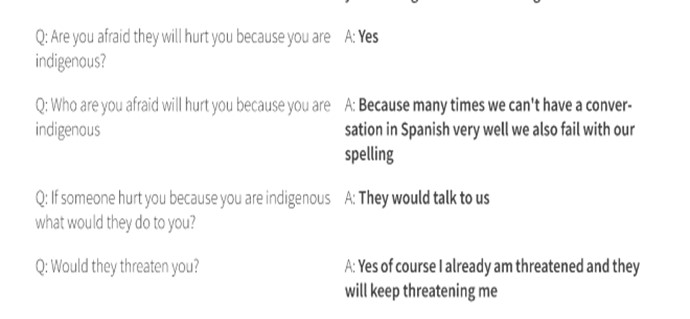

9. Indigenous families that speak a rare-language are being enrolled in FERM and required to proceed in a “second best” language.

Indigenous Peoples are disproportionally impacted by the new border policies of the Biden Administration. Many speak rare-languages and are therefore unable to access and utilize the CBP One application, leading Indigenous Peoples to be disproportionally subject to the asylum ban. Thirty-two out of eighty-five families whose information regarding their preferred language was tracked by AI Justice staff spoke an indigenous language other than Spanish. Many of these families reached out to Familias Seguras after they received a negative CFI determination or after the IJ affirmed their negative CFI determination. This data shows that many rare-language speakers are struggling to contact legal service organizations prior to critical junctures in the process. This data does not capture the potential hundreds of additional indigenous families who might never have received information regarding the FERM process in a language they can understand to even comprehend the need to reach out to legal services.

AI Justice staff has struggled to orient and consult with indigenous language speakers because of the difficulty in securing an interpreter to facilitate legal consultation and the tight timeline in preparing an individual for their CFI or NCFR. For example, one Quichua speaking family called AI Justice on a Sunday evening before their Tuesday morning CFI. We connected with them on Monday and were unable to secure an interpreter to help facilitate consultation, as a leading language interpretation service utilized by AI Justice requires at least 48 hours lead time to acquire rare-language interpreters.

In rare-language cases at the CFI stage, AI Justice staff regularly submit requests to reschedule the interview to allow for more time to secure an interpreter, or in the alternative, to issue the family an NTA based on the inability to obtain an interpreter. In multiple cases, upon not being able to connect with an interpreter, the AO issues a rare-language NTA to the family in accordance with required USCIS practices.

However, in the cases of rare-language speakers who have contacted AI Justice following a negative credible fear determination, staff have seen that often times families are pressured by AOs to proceed in a “second-best” language. AOs are required to inquire into all languages an individual may speak and the individual’s preferred language. If there is “evidence that the noncitizen communicated in a different language during the initial processing by CBP or ICE that is serviced by an interpreter contract” the AO must ask whether the asylum seeker is able and willing to proceed in the other language. The only safeguard in ensuring that the individual understood the interview questions is the AO asking if “the noncitizen understood the contents of the interview and was able to testify accurately and completely.” The issue with this circular framework is that individuals who are questioned in a language they do not fully understand cannot express what they have not understood, especially when they cannot comprehend the question. While the AO must close credible fear proceedings and issue a “rare-language” NTA in all cases where an individual’s preferred language is not serviced by translation services available to the asylum office, AI Justice’s case work reveals that many indigenous families in FERM have been compelled or coerced into participating in their CFI in Spanish.

I speak Quichua and Spanish, but Quichua is the language I know best and prefer. At my interview, I did not understand that I could request a Quichua interpreter. We have never used a translator before, and the translator they called spoke Spanish, so my husband and I proceeded with our interview in Spanish. It wasn’t until we had a negative decision and were able to talk to an attorney that they explained we could have a Quichua interpreter.

— Client enrolled in FERM Arlington

In the following example, the AO issued a negative decision after conducting an interview in Spanish despite the applicant disclosing that she spoke an indigenous language and stating during the CFI that she could not converse well in Spanish.

AI Justice has represented multiple indigenous language speakers at their NCFR, and largely had success in vacating negative CFI determinations based on language access issues. However, without the intervention of counsel, it is likely that these families would have proceeded with their NCFR in Spanish and received a different outcome. Again, it is unknown how many indigenous families have been quickly pushed through the FERM process without the ability to understand the proceedings, the need for legal counsel, or the right to proceed in their first and best language.

10. Additional training and infrastructure are needed to ensure family-friendly procedures throughout the credible fear process.

Special consideration is needed to ensure that families can effectively engage in their CFIs, specifically in relation to the length of time for these interviews, the need for confidentiality and in conjunction, childcare. Overall, families were underprepared for the logistics of attending their CFIs and the asylum office did not alter its procedures in consideration of the unique needs of the families.

In general, families spent between 4-10 hours at the asylum office on the day of their CFI, with six hours spent at the office on average. Based on 13 cases, the average CFI lasted approximately 3 hours. The longest interview lasted approximately 6.5 hours, with the shortest interview lasting approximately 2 hours. The average additional wait time at the asylum office was around 3 hours. This accounts for delays in the CFI starting and wait times following the interview but prior to receiving additional information regarding next steps in the FERM process.

Many families were unaware that the CFI process would take so long, and therefore were not prepared for the strains of the day. Families did not have access to food or water, or games/activities, etc. to keep their children otherwise engaged. None of the six families who were among the first enrolled in FERM that AI Justice interviewed for this report had access to food during their long day at the asylum office, with one family reporting that their AO even offered them fruits from his own lunch. AI Justice now provides advice to families regarding what to expect and how to prepare for the logistics of the CFI.

Access to childcare also varied for these families. For many parents, speaking candidly about the facts of their past persecution or fear of return is not possible in front of their children, as many children are unaware of the gravity of the situation in their home country and parents desire to shield them from this information. However, the ability for a parent to proceed with their CFI outside of the presence of their child/children depends on numerous factors, including not only if there is a trusted adult who can watch the child outside of the interview room, but also if the child is willing to consent to being separated from their parent and if the child’s immediate physical and mental health needs have previously been addressed.

For many children, being separated from their parents in the early days after arriving in the United States is traumatic. In multiple cases, during the CFI, children were left in the care of trusted adult family members; however, these children themselves had no prior relationship with these family members, leaving both the child and parent anxious about the separation. Various clients reported being distracted by thoughts of their child’s/children’s wellbeing despite the knowledge they were in the care of family members. In one case, a mother felt compelled to leave her child in the care of an employee of the asylum office, because she knew she would not be able to testify with her daughter present; however, even with her daughter waiting outside, she was unable to focus out of concern for her child’s wellbeing.

My two-year-old son was traumatized from our travels to the United States. He was very clingy to me and never wanted to leave my side. If I ever left his sight, he would immediately start to cry and try to find me. During my interview, I left my son with my brother-in-law in the waiting room. I told him I would be right back when I left, but as I walked away, I heard him start to cry. During the interview, I could not stop thinking about him. I knew he was safe with my brother-in-law, but I felt horrible knowing he was crying for me. I worried about whether or not he had a dirty diaper, whether he wanted his bottle, or had been fed. It was very hard to focus. My interview occurred only eight days after we arrived at my family’s house in New Jersey. Because I could not focus, I got a negative decision. But thankfully the judge reversed that decision. Today, two months since we arrived, my son is much more independent. He has gotten to know our family in New Jersey, and he is not afraid to be left alone with them. Because they have shown him love and he knows them now. I wish my interview had been later after my arrival, so I would have felt comfortable leaving my son in the care of my family during the process.

— Client placed in FERM Newark

On the day of my interview, I told the asylum officer I did not want my six-year-old daughter in the interview with me, because I knew I would have to talk about scary and difficult things, and I did not want her to see me cry and worry about me. I did not have anyone with me to watch her, so the officer asked a co-worker to sit with her in the waiting room. I did not want to leave my daughter with a person she had never met before, especially because my daughter was always wanting to be very close to me, but I did not feel like I had any other option. During my interview I was very nervous for my daughter. I was thinking about her every moment of the interview. I tried hard to focus on the questions I was being asked, but I kept wondering if my daughter was crying, if she was behaving well, what she might have been thinking about.

— Client placed in FERM Baltimore

Conversely, other parents had to proceed with their CFI with their child/children present in the room, either through choice or necessity. These parents struggled to share the details of their persecution fully during the CFI due to their child/children being in the room and being distracted by their child/children making noises, refusing to sit still, or demanding attention from their parent.

In addition, family members who proceed with their CFI in each other’s company are denied the right to a confidential interview. Having a family member present during the interview chills testimony. Confidentiality during a CFI is important for parents and children alike. AI Justice spoke with two clients whose children (aged 15 and 12) were substantively interviewed by the AO. In only one of these cases was the child asked if they preferred to speak in private, without their parent present. Children frequently have independent claims for protection. It is critical that children have a fair opportunity to present their claims, including by being able to present their claims outside of the presence of their parent(s) should they choose to do so.

Asylum offices traditionally do not have child-friendly spaces, such as a playroom with toys, games, or a television. These items would create meaningful distractions for children who are required to wait at the asylum office for hours. Resources such as tablets and noise-cancelling headphones could support parents who wish to testify with their child in the room without the child listening to their testimony.

AI Justice provides families with logistical advice on what to expect during the CFI, including the need to bring a trusted person to wait with the child outside of the interview room, bring food and drink to the interview, and wear warm clothing due to strong air conditioning. Staff has communicated with the asylum office to inform them of needed accommodations before their interview (for example, to inform USCIS that the client is uncomfortable proceeding with the CFI in the presence of their child or to request a female AO), that a client was lost or arriving late to their CFI, or that the family is in need of a break to access food or drink.

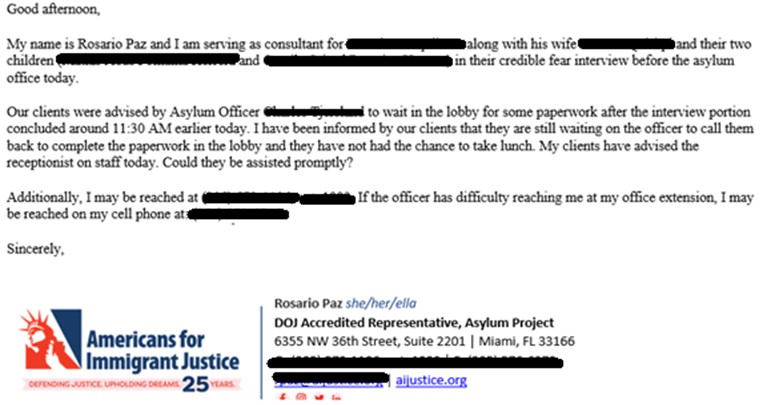

In the following example, the family arrived at the asylum office at 8 AM with their two children (aged 1 and 3). AI Justice had previously communicated with the AO in relation to the family’s status as Quichua speakers and the need for a rare-language interpreter. AI Justice staff telephonically accompanied the clients during their CFI, but the interview did not proceed due to lack of a Quichua interpreter. The family was asked to return to the lobby to await the issuance of a rare-language NTA. The family proceeded to wait for over seven hours without access to food or water. They attempted to ask the receptionist about their ability to leave and get food but could not communicate with her. The family called AI Justice around 3:30 PM to inform our staff they were still waiting—at which point AI Justice emailed the AO directly about the issue. An hour later, the AO confirmed service of the NTAs.

There are a number of logistical realities specific to families that FERM enrollees must navigate. While legal service organizations can often serve as a safety net for ancillary challenges that families may face, such as difficulties accessing transportation, childcare, or basic needs during the CFI, this falls outside the scope of legal service provision and puts additional strain on already overburdened organizations. The DHS must take the lead in developing the resources and infrastructure needed to support these families as they navigate the FERM process.

11. Families who live further afield from the asylum office or the immigration court face cost-prohibitive travel expenses.

In some FERM locations, families are required to travel more than an hour to arrive at the asylum office or immigration court. According to DHS, families who live within 75 miles of the local BI office may be enrolled in FERM for that specific location; however, travel times and cost from their home to the BI office, the asylum office or the immigration court could be substantial depending on the city and mode of transportation. For example, clients enrolled in FERM in Baltimore, Maryland are required to travel to the Arlington, Virginia asylum office for their CFI. Multiple clients have had to pay upwards of 200-300 dollars in taxi fare to travel to and from their CFI.

Yulia* was placed in FERM Washington, D.C. She resides in King George, VA, which is 70 miles from the Arlington asylum office and 65 miles from the Annandale Immigration Court. Depending on traffic, these trips typically take between 75-90 minutes. Yulia had to travel to the asylum office twice (once for her interview and again to pick up her CFI decision). She proceeded to a NCFR before the Annandale Immigration Court and had to travel there twice. Each trip cost her around $200-220 dollars.

Yulia first reached out to AI Justice after appearing before the IJ and informing him that she did not have legal counsel. He provided her AI Justice’s information. When staff first spoke with her, she had borrowed money from a friend to travel to another city to meet with another friend to borrow more money to be able to pay for her cab fare to Annandale for her second court hearing.

Many families have quickly gone into debt in order to facilitate their travel to their closest asylum office or immigration court, sacrificing their access to other necessities like clothing or medical care. As the FERM program expands, it remains unclear which asylum offices will be used to conduct CFIs and why certain field offices are not being utilized. For example, in the case of Baltimore enrollees, despite the existence of a USCIS field office in Baltimore, Maryland, families are required to travel to Arlington, Virginia. During a recent stakeholder engagement on the expansion of FERM to New Orleans, Louisiana and Houston, Texas, CBP officials would not confirm where New Orleans enrollees would participate in CFIS, despite acknowledging that CBP officials schedule CFI appointments on behalf of USCIS for FERM families.

12. ICE categorically subjects families in FERM to electronic surveillance and a home curfew without assessing the need on a case-by-case basis.

A majority of families who spoke with AI Justice found the FERM process to progress too quickly, and desired more time to prepare for the CFI both in terms of legal and logistical preparation. However, despite the speed of the process and the numerous hurdles discussed above, 100% of the families AI Justice has spoken with have tried in earnest to fully engage in the process and attended their CFI and, if scheduled, their NCFR—this includes 52 families who attended their CFI despite never having spoken with a legal service provider; 28 families who attended their CFI after receiving a KYR presentation from AI Justice; 7 families who attended their NCFR despite never having spoken with a legal service provider; and 12 families who attended their NCFR after only receiving a KYR presentation from AI Justice.

AI Justice has seen time and again that families are committed to complying with the tight timeline and other demands of the expedited FERM process. Here are just some of the hurdles they have overcome:

- Maria Angela* provided her son’s former Baltimore area address to CBP officials and was enrolled in FERM. Upon release, she was informed by her son that he had moved to Iowa. Maria Angela wasn’t able to get in touch with an attorney who could explain the process or advise her how to move her appointment location. She ultimately flew from Iowa to Arlington, Virginia to attend her CFI.

- Roberta* participated in her CFI and NCFR alongside her husband and child while extremely sick, fighting an infection. She ended up being hospitalized with sepsis the day after her negative CFI was vacated by an IJ.

- Javier* and his family arrived on time to what they believed to be their interview location. After waiting to be called for multiple hours, the family called AI Justice and learned that they were in fact at the Baltimore ICE office. The family made extraordinary efforts to arrive to the asylum office before close of business in order not to miss their chance to participate in their CFI.

- Lisbeth* was instructed by her ISAP officer to travel from Newark to New York City to apply for a Honduran passport. She spent the two days between her ISAP appointment, and her CFI attempting to comply and travelling to and from New York. Because of these requirements, she was not able to consult with an attorney until the evening before her CFI.

Despite the clear commitment of families to comply with the requirements of FERM, each family’s head of household is subjected to an overly restrictive and harmful GPS-enabled ankle monitor, a curfew, and electronic monitoring via a SmartLink device. The use of electronic ankle monitoring is harmful to the physical health of individuals subjected to its use—with 65% of respondents from a 2021 study experiencing a “constant, negative impact on their physical health while shackled” and 88% reporting that ankle monitoring negatively impacted their mental health.

One individual that AI Justice spoke with reported that vibrations of the ankle monitor were aggravating her pre-existing health issues and causing her to have severe headaches and difficulty breathing. Her blood pressure was elevated, and she almost fainted at her ISAP check-in. Another AI Justice client stated that being placed on an ankle monitor “didn’t feel good…people look at your differently. . . it’s really uncomfortable.”

While AI Justice has only been successful in one of two requests to have a family unenrolled in FERM due to a serious medical condition making the ankle monitor unsafe, without access to legal advocacy, it is much less likely that these issues will be escalated for ICE’s consideration. Although AI Justice, like many immigrant’s rights organizations, condemns the use of electronic monitoring all together, the failure to make a case-by-case individualized assessment regarding each individual families placement on an ankle monitor, home curfew, and electronic surveillance greatly increases the number of individuals who are unnecessarily subjected to them.

Conclusion

At its core, the FERM program is deeply problematic in that it is predicated on the use of expedited removal—a process that consistently denies asylum seekers due process and the right to have their claims for protection fully adjudicated. Additionally troubling is the Biden Administration’s expanded use of expedited removal in conjunction with the asylum ban to punish asylum seekers who enter without inspection and deter others from attempting to seek safety. However, within this deeply flawed system, the FERM program is predicated on the presumption of release for asylum-seeking families into the community to allow them to present their claims outside the confinements of immigration detention. Family detention, even for short periods of time, is deeply traumatic and inhumane for families. Release into the community allows families greater access to counsel, support systems, evidence, and resources to more effectively prepare for the presentation of their asylum claims. However, families need sufficient time in order to access these indispensable resources.

Over the course of eleven weeks, AI Justice spoke with approximately 164 families subject to the FERM process. While this represents just a fraction of the total number of families who have gone or are going through this process, the experiences of the Familias Seguras staff in orienting and representing FERM families sheds light on the numerous ways in which the policy in its current form fails to consider the unique vulnerabilities and specific needs of families and children and how the truncated timeline around which the process is built unduly restricts meaningfully access to counsel. Key aspects of the policy, including the categorical use of surveillance mechanisms, the potential for family separation caused by the narrow definition of what constitutes a family unit, and the enrollment of Indigenous Peoples and rare-language speakers, urgently need to be reassessed.