By Alex Leary and Steve Bousquet

June 29, 2018

Florida’s key role in the national detention system wasn’t publicly known until news broke in mid-June that more than 1,000 children were housed in a dorm-like former job training center in Homestead, including at least 70 kids who were taken from their families.

No one noticed.

Five months ago, the federal government sent an advisory to Gov. Rick Scott and Florida members of Congress: It was re-opening a shelter for “unaccompanied alien children” 35 miles south of Miami.

“There is no set date for UACs to arrive at the facility,” a letter read, pledging “accountability and transparency for program operations.”

The Homestead shelter, run by a private Florida contractor for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, has become a flash point in an uproar over President Donald Trump’s immigration policy. Hundreds of migrant children sent there went unnoticed until they were joined by dozens more torn from their parents at the border in recent weeks.

The outcry over child separation has revealed a disturbing bigger picture. America’s immigration enforcement system is a complex patchwork involving multiple federal agencies, local sheriffs, nonprofits and, increasingly, politically influential corporations like Florida-based GEO Group.

The system exists in a bureaucratic netherworld. Neither Scott’s office nor the Department of Children and Families provided a complete list of federal immigration facilities in Florida, because they said the immigrants are not in the state system.

Yet getting federal officials to provide details about the system is difficult — and made more so by outsourcing. Most requests for information must go through a formal process that takes months or even years.

Florida’s key role in the national detention system wasn’t publicly known until news broke in mid-June that more than 1,000 children were housed in a dorm-like former job training center in Homestead, including at least 70 kids who were taken from their families.

Politicians, mainly Democrats, rushed to the shelters and demanded action. Others, including the Republican governor, said they opposed child separation but have not taken much action, seeming to underscore the treacherous politics of immigration in an election year.

“It’s a controversial and complicated issue,” said Frank Sharry, executive director of immigration reform group America’s Voice. “We’re a country that is at war with itself over how we reconcile being a nation of immigrants and nation of laws. The ‘keep ’em out, let them in’ fight results in conflicting mandates and a lack of coherence.”

A scattered system

Part of the challenge in understanding the system is how scattered it has become, with two different tracks for children and adults and various layers to each.

Children from poverty and violence-torn Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador began to flood the border in 2014, mostly unaccompanied by adults. President Barack Obama’s administration sent them to shelters across the country to be cared for while a family member or sponsor in the U.S. could be located. Some ended up in Tampa and Clearwater, though details are murky.

Trump added a new and explosive factor, by splitting children who arrived with adults — a hardball tactic to deter other immigrants from making the dangerous journey across the border.

Undocumented children are overseen by a federal HHS division called the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Care can be outsourced, either to nonprofits or for-profit companies such as Comprehensive Health Services of Cape Canaveral, which runs the Homestead shelter under a contract worth more than $30 million.

Many more undocumented adults are apprehended at the border, picked up after traffic stops or for committing a crime or simply swept up in raids across the country, which have grown more frequent after Trump took office.

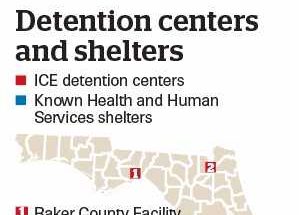

Some are held in county jails in Florida in such far-flung places as Crawfordville, Macclenny, Naples and the Keys, making it difficult for families to reach them.

Florida saw the largest percentage increase of immigration arrests in the country in 2017, according to a Pew Research Center report. These adults are processed through the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, a division of Homeland Security.

![[Tampa Bay Times]](https://s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/tbt/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/29162011/detention.jpg)

The pink-painted Broward facility, which GEO operates on a contract of more than $20 million annually, has been a magnet for controversy in recent years as it has handled hundreds of people subjected to long stays despite being detained for minor offenses.

In 2012, a detainee from Argentina went on hunger strike. Americans for Immigrant Justice, a Miami group that provides support to undocumented immigrants, produced a report three years ago that said detainees were sexually assaulted, denied legal assistance and given substandard medical care.

“We strongly dispute these allegations,” GEO Group spokesman Pablo Paez wrote in a statement to the Tampa Bay Times. “On a daily basis, our dedicated employees deliver high quality services, including around-the-clock medical care, that comply with performance-based standards set by the federal government and adhere to guidelines set by leading third-party accreditation agencies.”

Paez referred a request for contracts, inspection reports and audits to ICE. That agency, in turn, said the Times must request them under the Freedom of Information Act, a process that can take months or longer.

ICE standards vary by location and can be advisory in nature, experts say, and even material that is made public may not include all details as the private groups assert commercial trade secret protections.

Other ICE detention centers are contracted through a handful of county sheriffs who rent space in jails. Those counties include Baker, near Jacksonville; Glades, on the rim of Lake Okeechobee; Collier, in southwest Florida; Monroe, in the Keys; Wakulla, south of Tallahassee; and Pinellas in Tampa Bay, which generally houses 50 to 60 detainees a day and is paid $80 per day for each.

Pinellas Sheriff Bob Gualtieri said the county jail in Clearwater meets or exceeds all federal standards, and that his agency has a productive working relationship with ICE, which visits at least once a year. “They come in and inspect our jail to be sure we are meeting the standards.”

But it’s wrong for immigrants to be housed in jails with people accused of criminal violations, argued Jessica Shulruff Schneider, an attorney and director of detention for Americans for Immigrant Justice.

“Immigration laws are civil. They’re not criminal. We generally believe that immigrants should not be held in a detained setting while they are awaiting a hearing on an immigration case. Most of them should be released on their own recognizance or some sort of bond so they can remain with their families.”

Still, many Americans agree with a tougher approach that Trump made a centerpiece of his campaign.

“Do we want to have borders or not?” asked state Rep. Joe Gruters, a Sarasota Republican who has sponsored several enforcement measures. “We should reward the people who go through the proper legal channels. I blame this long-term problem not on the people who want to come over here — you’ve got to have compassion — but on Congress and its inability to make hard decisions.”

Costs and profits

Critics say this is costly and ineffective. U.S. Rep. Ted Deutch, D-Boca Raton, points to a Congressionally-directed mandate to fund 34,000 detention beds per day, a quota no other law enforcement agency faces. An alternative to the $2 billion annual detention cost, Deutch said, is to require the use of GPS ankle bracelets and other less costly monitoring measures while immigrants await court hearings.

“Are we including these provisions in the appropriations bill to ensure undocumented immigrants show up for proceedings or is it for a guaranteed funding source for private contractors?” Deutch said in an interview.

Nationally, about 70 percent of detainees are in privately run facilities — and that could grow. Last week the Trump administration said it was looking to add 15,000 beds for family detention, a potential boon to GEO Group and CoreCivic, a private prison operator formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America.

Both have become heavy players in the political process, donating to candidates, largely Republicans, and spending millions on influencing policy; among the lobbyists it employs is Florida resident Brian Ballard, who is close to Trump.

GEO Group employees and its political action committee has given more than $250,000 to the campaigns of Sen. Marco Rubio. Gov. Scott has received more than $800,000 while Sen. Bill Nelson, whom Scott is challenging this November, has received $19,000, according to a Times/Herald analysis of federal campaign data.

Trump is a big recipient of GEO-asssociated money, and last year the company held its annual conference at Trump’s Doral golf resort. (It denies any attempt to influence policy.)

Trump has reversed the child separation policy but the job of reuniting more than 2,000 kids with their parents remains outstanding and protests continue. HHS has launched a review of shelters and training of contractors, overseeing 12,000 migrant children overall.

“Today the focus is on this issue because it was so painful to watch,” said Deutch. “Maybe this is just a reminder that we have contracted out the responsibility for an enormous part of our immigration system and perhaps we don’t have a good enough grasp of how that plays out.”

Read it via Tampa Bay Times here.